1954 Italian expedition to K2

On the 1954 Italian expedition to K2 (led by Ardito Desio), Achille Compagnoni and Lino Lacedelli became the first people to reach the summit of K2, 8,611 metres (28,251 ft), the second-highest mountain in the world. They reached the summit on 31 July 1954. K2 is more difficult to climb than Mount Everest, 8,849 metres (29,032 ft), which had first been climbed by a British expedition in 1953.

Three earlier unsuccessful American attempts on the mountain had identified a good route to use. Desio felt Italy's earlier exploration of the Karakoram region gave good reason to mount a major expedition which he did on a grand scale, following the American route up the south-east ridge. Progress towards the summit was repeatedly interrupted by storms, and one member of the team died rather unexpectedly. Desio considered abandoning the expedition so as to try again by returning later in the year, but weather conditions improved allowing them to edge closer to the top of the mountain. At last, the two lead climbers reached the summit as the sun was about to set and they had to descend in the dark. They and two colleagues went on to suffer from severe frostbite.

The fact that the summit had been reached was never doubted – Compagnoni and Lacedelli had been seen by their colleagues near the summit and they had taken photographs and even a movie film from the top – but all the same the expedition became mired in argument. After a prolonged controversy, the official 1954 account of the expedition eventually became discredited, and a second official account was published in 2007 which largely confirmed the claims another member of the expedition, Walter Bonatti, had been making for over fifty years.

Background

K2

K2 is on the border between China and what was, in 1954, the newly independent Pakistan. At 8,611 metres (28,251 ft), it is the highest point of the Karakoram range and the second-highest mountain in the world.[1] The mountain had been spotted in 1856 by the Great Trigonometrical Survey to Kashmir,[note 1] and by 1861 Henry Godwin-Austen had reached the Baltoro Glacier and was able to get a clear view of K2 from the slopes of Masherbrum.[note 2] He could see that the descending glacier eventually drained to the Indus River, so the mountain was in the British Empire.[4]

| History of climbing K2 | |

|---|---|

Television programs | |

1954 expedition starts at 18:09 minutes | |

1954 expedition starts at 43:00 minutes[note 3] | |

Charlie Houston talking about 1953 expedition (start 05:50) and narrating film (starting 15:35)[note 4] |

The first serious attempt to climb the mountain was in 1902 by a party including Aleister Crowley, who later became notorious as "the Wickedest Man in the World". The expedition examined ascent routes both north and south of the mountain and made best progress up the north-east ridge before they were forced to abandon their efforts.[8] Since that time, K2 has developed the reputation of being a more difficult mountain to climb than Mount Everest – every route to the summit is tough.[9][note 5] K2 is farther north than the Himalayan mountains so the climate is colder; the Karakoram range is wider than the Himalayan so more ice and snow is trapped there.[12]

Before the successful Italian ascent, the expedition that had previously climbed highest on K2 had been the 1939 American Karakoram expedition which reached 8,370 metres (27,450 ft).[13]

Previous Italian expeditions in the Baltoro Muztagh Karakoram

In 1890, Roberto Lerco entered the Baltoro Muztagh region of the Karakoram. He reached the foot of K2 and may even have climbed a short way up its south-east spur, but he did not leave an account of his journey.[14][15]

In 1909, the Duke of the Abruzzi expedition again explored various routes before reaching about 6,250 metres (20,510 ft) on the south-east ridge before deciding the mountain was unclimbable. This route later became known as the Abruzzi Ridge (or Abruzzi Spur) and eventually became regarded as the standard route to the summit.[1]

In 1929, Aimone di Savoia-Aosta, the nephew of the Duke of the Abruzzi, led an expedition to explore the upper Baltoro Glacier, near to K2. The geologist on the party was Ardito Desio, and he came to feel that there was an Italian claim for attempts on the mountain.[16] It was only in 1939 that Desio could interest Italy's governing body for mountaineering, the Club Alpino Italiano (CAI), but World War II and the Partition of India delayed things further.[17] Later, in 1952, Desio travelled to Pakistan as a preliminary for leading a full expedition in 1953 only to discover that the Americans had already booked the single climbing permit for that year. He returned in 1953 with Riccardo Cassin to reconnoitre the lower slopes of K2.[18][19] At that time, Cassin was the greatest Italian mountaineer there had been, and yet in Desio's report of the reconnaissance, Cassin is not mentioned except to say "I had chosen Ricardo Cassin, a climber, to whose travelling expenses the Italian Alpine Club had generously contributed".[20] It was only after his return to Italy that Desio heard he had been granted the permit for the 1954 summit attempt.[21]

Preparation for 1954 expedition

In Rawalpindi, at the start of his 1953 visit to Pakistan, Desio had met Charlie Houston, leader of the unsuccessful 1953 American Karakoram expedition who was returning from K2. On both the 1938 expedition and the 1953 expedition, Houston had climbed the entire Abruzzi Ridge, scaling its most difficult cliffs, House's Chimney, and had been able to reach about 7,900 metres (26,000 ft) from where a feasible route to the summit could be observed.[22] Even though the American was planning another attempt on the summit for 1954, he was generous in sharing his experience and photographs with Desio, an obvious rival.[19][23]

Desio planned a far larger expedition than the American ones – the cost estimate of 100 million lira (equivalent to US$1.8 million in 2023) was eight times greater than Houston's and three times greater than the successful 1953 British Everest expedition.[24] It was sponsored by the CAI and it became a matter of national prestige, also involving the Italian Olympic Committee and the Italian National Research Council.[25] The French success on Annapurna in 1950 and British success on Mount Everest in 1953 had had immense impacts in their respective countries.[26] Desio wrote "the expedition will of necessity be organised along military lines"; as in the 1950 French Annapurna expedition, the Italian climbers were all required to formally pledge allegiance to their leader, Desio.[27] Scientific research – geography and geology – was to be as important as reaching the top of the mountain. Indeed, it seems that Desio, professor of geology at Milan, held climbers in rather low regard.[note 6][29][30]

There were to be eleven climbers, all of them Italian, none of whom had been to Himalaya before: Enrico Abram (32 years), Ugo Angelino (32), Walter Bonatti (24), Achille Compagnoni (40), Cirillo Floreanini (30), Pino Gallotti (36), Lino Lacedelli (29), Mario Puchoz (36), Ubaldo Rey (31), Gino Soldà (47) and Sergio Viotto (26). There were ten Pakistani Hunza high-altitude porters, with Amir Mahdi (41) turning out to be the most prominent.[note 8] Also on the team was a filmmaker, Mario Fantin, and a team doctor, Guido Pagani. The scientific team, in addition to Desio (who was 57 years old), comprised Paolo Graziosi (ethnographer), Antonio Marussi (geophysicist), Bruno Zanettin (petrologist), and Francesco Lombardi (topographer). Muhammad Ata-Ullah was the Pakistani liaison officer.[32][33][34] Riccardo Cassin, the pre-eminent Italian Alpinist, had been nominated by the CAI as climbing leader but, after Desio's rigorous selection procedures, he was rejected, supposedly on medical grounds, though it was speculated that it had really been to avoid Desio being outshone.[35][36]

The plan was for nearly 5 kilometres (3 mi) of fixed nylon ropes to be placed up the complete length of the Abruzzi Ridge and some way beyond and, where possible, loads on sledges were to be winched along these ropes. Each camp was to be fully established before the next higher camp was occupied. Open-circuit oxygen systems were used and members were equipped with two-way radio.[37]

The expedition left Italy by air in April 1954 and the baggage, which went by sea, arrived in Karachi on 13 April and then travelled by rail to Rawalpindi.[38][39]

Official published accounts of the climb

Desio wrote the official account of the ascent in his 1954 book La Conquista del K2,[40][note 9] but this account was disputed over many years by Bonatti and, eventually, Lacedelli and others. That Compagnoni and Lacedelli had reached the summit of K2 was not in dispute – at issue was the extent to which they had depended on support from other climbers high on the mountain, how they had treated Bonatti and Madhi, whether they used oxygen all the way to the top, and whether Desio's book was accurate and fair. The matter became increasingly controversial with a great deal of press criticism, often uninformed. Desio died in 2001 at the age of 104 and, eventually, in 2004 the CAI appointed three experts, called "I Tre Saggi" (the three wise men), to investigate. They produced a 39-page report in April 2004,[42][note 10] but the CAI delayed until 2007 its publication of K2 – Una Storia Finita which included and accepted the Tre Saggi report.[44][note 11]

The account of the climb given here is based on recent sources which have been able to take into account the CAI's second official report, K2 – Una Storia Finita (2007). The scientific (geographical and geological) aspects of the expedition are not covered nor is the controversy which went on for over fifty years after the return to Italy.

Approach to K2

After delays due to poor weather, on 27 April the expedition flew by DC-3 from Rawalpindi to Skardu. Desio took the opportunity of using the aircraft to survey the region's topography and snow conditions, which seemed similar to those in Houston's photographs of the previous year. The mountains were higher than the aircraft's service ceiling so they needed to circumnavigate K2.[46][47] The scientific party then departed on their separate itinerary. Five hundred locally appointed Balti porters carried over 12 metric tons (13 short tons) of equipment, including 230 oxygen cylinders, via Askole and Concordia towards Base Camp on the Godwin-Austen Glacier.[48][49]

Between Skardu and Askole several bridges had been built in the previous year so this part of the journey was much quicker than before. After Askole they were unable to buy food locally for the porters so they needed to hire another hundred men simply to carry flour for the main porters to make their chapatis. So as to minimise weight, Desio had provided little for the porters apart from food, a blanket each, and tarpaulins to be used as tents. They had no protective clothes. Unfortunately there was bad weather – snow as well as heavy rain whereas the previous year the weather had been fine and sunny – the porters started refusing to go on, even after being offered backsheesh. At Urdukas 120 porters turned back and the others halted – next morning some porters wandered back down and nobody would proceed. On Ata-Ullah's advice the sahibs went on ahead and, for a while, the porters disconsolately followed at a distance. Then there was a critical problem. The sun came out and, with it shining on the snow, the porters were struck with snow blindness. Snow goggles had been brought for them but half of them had been left behind to save weight. When eventually only one porter remained with the party they had to recruit fresh porters from back at Askole. By the time they had struggled to get Base Camp established on 28 May they had been delayed by fifteen days.[48][50][51][52]

Line of ascent of K2

The route to be taken was the same as for the American expeditions with camps planned for similar locations.[53]

| Locations of camps on mountain | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camp | Altitude [note 12] |

Established | Location | |

| metres | feet | |||

| Base | 5,000 | 16,400[54] | 28 May[51] | Godwin-Austen Glacier[55] |

| I | 5,400 | 17,700[56] | 30 May[57] | foot of Abruzzi Ridge[58] |

| II | 6,100 | 19,900[59] | 2 June[60] | sheltered spot on Ridge |

| III | 6,300 | 20,700[61] | ||

| IV | 6,450 | 21,150[62] | 16 June[57] | below House's Chimney |

| V | 6,700 | 22,000[63] | 4 July[64] | right above House's Chimney, start of sharp part of Ridge[65][66] |

| VI | 7,100 | 23,300[67] | 7 July[68] | base of Black Tower (or Pyramid)[69] |

| VII | 7,345[70] | 24,098 | 26 July[71] | above Ridge and below Shoulder at 7,600 metres (25,000 ft)[72] |

| VIII | 7,627[70] [note 13] |

25,023 | 28 July[51] | foot of ice wall overlooking a crevasse[75] |

| IX | 8,150[76] [note 14] |

26,740 | 30 July[78] | above rocky slabs near start of Bottleneck[79] |

| Summit | 8,611 | 28,251[9] | 31 July[80] | |

The Abruzzi Ridge can be climbed by strong climbers from Base Camp up to Camp VI in a few hours of good weather but it can also be a dangerous place to be. Between Camp IV and Camp VII the ridge is sharp, steep and unrelenting with exposure and rockfall being problems on the lower section. Strong winds can be a major difficulty – K2 partly protects the major eight-thousanders to the south but is itself very exposed to storms.[81]

Progress on the mountain

Ascending the mountain

By 16 June Camp IV was established at the foot of House's Chimney, using the winch to haul supplies up to Camp II. In 1953 Houston's party had found the Hunzas to be better on the mountain than had been expected. However, Desio felt let down – part of the difficulty was that English was their only language in common and, apart from Desio himself, no one was fluent in English. Tragedy struck the expedition at an early stage: after Puchoz had descended to Camp II he developed problems with his throat and his condition deteriorated until, despite good medical treatment and ample medicines and oxygen, he died with symptoms of pneumonia on 21 June.[note 15] The next day everyone descended to Base Camp just as a fierce snow storm erupted. When the storm abated they were able to recover Puchoz's body to Base Camp and on 27 June they ascended to bury him beside the memorial cairn to Art Gilkey who had died on the 1953 American expedition.[82][83]

The expedition was by now almost a month behind schedule so Desio announced that the climb should be resumed immediately after the funeral. However, apart from Compagnoni, none of the climbers were willing to do this and Abram spoke up on their behalf. Desio had an authoritarian approach to leadership (behind his back he was called "il Ducetto", "little Mussolini"). He was in the habit of issuing written encouragements and orders. For example, on one occasion he pinned up a notice:

"Remember if you succeed in scaling the peak – as I am confident you will – the entire world will hail you as champions of your race and your fame will endure throughout your lives and long after you're dead. Thus even if you never achieve anything else of note, you will be able to say that you have not lived in vain."

When interviewed later about it Lacedelli said "We just ignored him and got on with it".[84]

The climbers again spread out across the various camps and Compagnoni and Rey scaled House's Chimney but then another storm confined everyone to their tents. On 5 July, Compagnoni (who Desio had nominated to lead the high-level climbing), Abram and Gallotti established Camp V and then two days later reached Camp VI with fixed ropes now running all the way up from Camp I. They used the ropes from the 1953 expedition to reach camp VII although, on descending, the ropes slipped from their anchor points causing Floreanini to fall 200 metres (700 ft) but suffering no very serious injury.[64][85]

On 18 July Compagnoni and Rey, followed by Bonatti and Lacedelli, set ropes as high as the American Camp VIII at the base of the summit plateau. Camp VI had been at the site of the American Camp VII but they moved it higher to avoid what they considered was a dangerous location.[86] Successive severe storms made progress much slower than expected and Desio wrote to the CAI saying he was contemplating returning to Italy and staging a new assault in the autumn with a smaller team of fresh climbers, but using the existing fixed ropes. But then the weather improved.[87] On 28 July Camp VIII was established at 7,627 metres (25,023 ft) for a summit attempt by Compagnoni and Lacedelli. Next day they climbed higher but, unable to find a good location for their highest camp, Camp IX, they left their rucksacks and returned to Camp VIII, now realising they would need supplementary oxygen for the summit. The place where they had been trying to set Camp IX was beside a wall of ice at 8,000 metres (26,000 ft), beside what later became known as the Bottleneck.[88][89][90] Also on 29 July four climbers at Camp VII went up with two oxygen sets (each weighing 18 kilograms (40 lb)), a tent and extra food towards Camp VIII but Abram and Rey had to turn back and only Bonatti and Gallotti got there – they had needed to abandon the oxygen sets at about 7,400 metres (24,300 ft). By evening Mahdi and Isakhan reached Camp VII.[88]

Preparing for the summit attempt

For 30 July the four men at Camp VIII agreed that while Compagnoni and Lacedelli would climb to try to establish Camp IX, Bonatti and Gallotti would descend to fetch the oxygen just above Camp VII and then carry the heavy oxygen equipment all the way up to Camp IX, via Camp VIII. The fetching of the oxygen would be a far greater challenge than the establishment of the high camp – it would involve a descent of 180 metres (600 ft) followed by an ascent of 490 metres (1,600 ft). They would tell climbers at Camp VII to bring up more supplies to VIII. Meanwhile, Compagnoni and Lacedelli would establish Camp IX at a lower level of 7,900 metres (25,900 ft) to reduce the height the oxygen needed to be carried.[91] In the event they established their high camp not at the lower level, where there was deep powdery snow, but at 8,150 metres (26,740 ft) across a difficult traverse over dangerous slab rocks which took almost an hour to achieve. They had very little food and, although they had oxygen masks with them, not the actual gas cylinders.[92][93]

Bonatti, Gallotti, Abram, Mahdi and Isakhan all met and reached Camp VIII by noon on 30 July. At 15:30 Bonatti, Abram and Mahdi went on with the oxygen cylinders towards Camp IX.[94] The Hunzas had not been provided with high-altitude boots and to induce Mahdi to go on higher Bonatti had offered him a cash bonus and had also hinted that he might be allowed to go right up to the summit. They went without a tent or sleeping bags.[95] At about 16:30 they shouted and heard a reply from the summit team at Camp IX but could not locate them nor see any tracks to follow. They climbed higher but by 18:30 the sun was setting and Abram had to go down because of frostbite. They now could see tracks in the snow but still no tent and it would be dark imminently. Mahdi was starting to panic. On dangerous terrain sloping at 50° and still with the heavy oxygen sets they called again but had to come to a halt at 8,100 metres (26,600 ft).[94]

Bonatti dug out a small step in the ice in preparation for an emergency overnight bivouac without a tent or sleeping bags. After more shouting, at 22:00 a flashlight shone from quite nearby and slightly higher up the mountain and they could hear Lacedelli shouting to tell them to leave the oxygen and go back down. After that the light went out and there was silence. Bonatti and Mahdi spent the rest of the night in the open until at 05:30, against Bonatti's advice, Mahdi started going down by himself in the dark to Camp VIII.[94] Bonatti waited until about 06:30 when it was getting light before he dug the oxygen sets out of the snow and descended. While he was going down he heard a shout from somewhere above but could not see anyone. Mahdi reached Camp VIII only slightly before Bonatti at about 07:30.[94][96]

Reaching the summit

At about 06:30–06:45 on 31 July Compagnoni and Lacedelli left their tent and saw someone (they could not tell who) descending and were shocked to think they must have spent the night in the open.[97][98][note 16] They recovered the gas cylinders between about 07:15 and 07:45, and from there set off for the summit at about 08:30, now breathing supplementary oxygen.[97] To save weight they abandoned their rucksacks and, for nourishment, only took sweets. The route through the Bottleneck was blocked with snow and they could not climb the cliffs as Wiessner had done in 1939. Eventually they found a line close to Wiessner's up though mixed ice and rock.[100] The people below at Camp VIII were briefly able to see them ascending the final slope just before Compagnoni and Lacedelli reached the summit arm in arm at about 18:00, Saturday, 31 July. Gallotti wrote in his diary:

On the final slope, which was incredibly steep looking, first one tiny dot, and then a second, slowly made their way up. I may see many more things in this life, but nothing will ever move me in this same way. I cried silently, the teardrops falling on my chest.

They took a few photos and a brief movie film as the sun was setting. Lacedelli wanted to go down as soon as possible but Compagnoni said he wanted to spend the night on the summit. Only after being threatened with Lacedelli's ice-axe did he turn to descend.[97][101]

Descending the mountain

In the darkness they headed down this time descending Bottleneck Couloir[102] and after a while their oxygen ran out.[note 18] They had great difficulty crossing a crevasse and descending the ice wall just above Camp VIII and both men fell but eventually their companions heard their shouts and emerged to help them back to Camp VIII just after 23:00.[103] Next day, in poor weather, they descended the fixed ropes to Camp IV by 11:00. By 2 August everyone was back at Base Camp.[104] Compagnoni, Lacedelli and Bonatti had serious frostbite to their hands but Mahdi's feet were also affected and his condition was much worse.[105]

Return home

On 3 August the news of the success reached Italy but, in accordance with an earlier collective agreement suggested by Floreanini, the names of the climbers who had reached the summit were kept secret. Their triumph was very big news in Italy, but internationally it made less impact than the previous year's ascent of Everest, which had been boosted by the coronation of Elizabeth II. After some recuperation the party left base camp on 11 August[note 19] with Compagnoni going ahead, wanting to hasten to Italy for hospital treatment. Lacedelli, with Pagnini's medical support, preferred to take things more slowly to try to avoid unnecessary amputations of his fingers. Mahdi was much the worst affected and went to hospital in Skardu, eventually having nearly all his fingers and toes amputated.[106][107]

The press speculated, mostly correctly, on who had been in the summit party and when Compagnoni flew into Rome in early September he was treated as a hero. The main party arrived at Genoa by sea later in September and Desio flew in to Rome in October. At the height of the celebrations on 12 October Desio announced the names of those who had reached the summit. This news flopped because it had been repeatedly reported (through speculation) for months. Earlier the CAI, while still refusing to name who they were, had published a photo of Compagnoni and Lacedelli on the summit.[108]

However, before the party had left Pakistan, a scandal had been making headlines in the subcontinent's press. Mahdi had been reported as saying he had been within 30 metres (100 ft) of the summit but his two Italian companions had not allowed him to go any higher. This received very little attention internationally but the matter was serious enough for the Italian ambassador to Karachi to hold an inquiry. He did not speak to Mahdi but interviewed the Italians involved as well as Ata-Ullah, the liaison officer, to whom Mahdi had made his complaints.[108] The report concluded that no porters had been near the summit; Bonatti and Mahdi turned back below Camp IX leaving the oxygen respirators; and Mahdi had been wild and undisciplined trying to escape the bivouac. This satisfied the Pakistan government and even the press calmed down.[109] However, it was only very many years later that Bonatti came to believe that in reality Desio regarded the report as a cover-up (one that Desio approved of) for what he believed had been Bonatti's attempt to sabotage the expedition. This was to cause repercussions over the next 50 years.[109][110][111]

It was not until 1977 that the second ascent of K2 was made – once again via the Abruzzi ridge – by a well-equipped Japanese expedition, which took 59 climbers and 1,500 porters.[112]

Notes

- ^ The tallest mountains measured were called "K1" and "K2" and the higher one turned out to be K2.[2]

- ^ Hence the earlier name of K2 was "Mount Godwin-Austen".[3]

- ^ Video hosted on Vimeo at https://vimeo.com/54661540

- ^ Video hosted on Google at https://storage.googleapis.com/cctv-library/cctv/library/2005/01/DrHouston_01092005/DrHouston_01092005.broadband.mp4

- ^ K2 may be the most challenging of all the eight thousand meter mountains, though Annapurna has a higher death rate for climbers than either Everest or K2.[10] Kauffman and Putnam liken the comparison between Everest and K2 to that between Mont Blanc and the Matterhorn in the Alps.[11]

- ^ In 1953 Desio had travelled by air in Italy and from Karachi to Rawalpindi, while Cassin had to go by train. Both men flew from Rome to Karachi, however.[28]

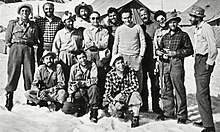

- ^ In the June group photo the team members were: standing, left to right: Achille Compagnoni, Ugo Angelino, Gino Pagani (doctor), Mario Fantin (film maker), Ardito Desio (leader, arms crossed), Erich Abram, Gino Solda, Lino Lacedelli, Walter Bonatti, Sergio Viotto, Pino Gallotti; front: Ubaldo Rey, Cirillo Floreanini, Mario Puchoz.

- ^ Mahdi (also transliterated Mehdi) came from Hassanabad.[31] Hunzas did the equivalent work of Nepali Sherpas.

- ^ The official account is translated into English as Victory over K2[41]

- ^ I Tre Saggi were Fosco Maraini, Luigi Zanzi and Alberto Monticone.[43]

- ^ An English description of K2 – Una Storia Finita including a translation of much of its contents is given in Marshall's K2 – a Final Report which also includes an extended commentary that, in short, confirms Bonatti's version of events.[45]

- ^ Altitudes have needed to be drawn from a variety of sources – later sources have been preferred. The figures are referenced in either the "metres" or "feet" column according to the source. The unreferenced cell is a mathematical conversion of the associated figure.

- ^ The oxygen bottles were left somewhere between 7,375 and 7,400 m.[73] According to Bonatti the Camp VIII was originally to be at about 7,700 metres (25,400 ft).[74]

- ^ The original plan had been to site Camp IX at 8,000 – 8,100 m and the plan of 30 July was to site it instead at 7,900 m. Bonatti and Mahdi's bivouac was at 8,100 m.[77]

- ^ Puchoz succumbed to what is now thought to be pulmonary edema.[51]

- ^ Desio's account says they left Camp IX at 05:00[99] and this discrepancy of times led to the later trouble about whether the supplementary oxygen would have run out before reaching the summit.

- ^ The team members were, from left standing: Ubaldo Rey, Ugo Angelino, Walter Bonatti, Ardito Desio (leader, arms crossed), Lino Lacedelli, Erich Abram, Gino Soldà, Achille Compagnoni, Cirillo Floreanini. From left seated: Sergio Viotto, Mario Fantin (film maker), Guido Pagani (doctor), Pino Gallotti.

- ^ Both climbers said their oxygen ran out (at very similar times) before they reached the summit. A good deal of the controversy over the coming years was about how long the oxygen really lasted.[97]

- ^ Desio had departed on 7 August to resume his geological research for the scientific aspects of the expedition.

References

Citations

- ^ a b Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 18–22.

- ^ Isserman & Weaver (2008), p. 18.

- ^ Isserman & Weaver (2008), p. 21.

- ^ Isserman & Weaver (2008), pp. 18–21.

- ^ Vogel & Aaronson (2000).

- ^ Conefrey (2001).

- ^ Houston (2005).

- ^ Isserman & Weaver (2008), pp. 58–60.

- ^ a b Conefrey (2015), p. xii.

- ^ Day, Henry (2010). "Annapurna Anniversaries" (PDF). Alpine Journal: 181–189. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ Kauffman & Putnam (1992), p. 18.

- ^ Curran (1995), 156/3989.

- ^ Kauffman & Putnam (1992), p. 117.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), p. xvi.

- ^ Isserman & Weaver (2008), p. 42.

- ^ Isserman & Weaver (2008), pp. 198–199.

- ^ Sale (2011), pp. 102–103.

- ^ "Biografia Desio". www.arditodesio.it (in Italian). Ardito Desio Association. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ a b Isserman & Weaver (2008), p. 314.

- ^ Viesturs (2009), p. 197.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), p. 188.

- ^ Isserman & Weaver (2008), pp. 207–215, 314.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), p. 186.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), p. 189.

- ^ Isserman & Weaver (2008), pp. 314–315.

- ^ Viesturs (2009), p. 194.

- ^ Isserman & Weaver (2008), pp. 243, 314–315.

- ^ Sale (2011), p. 103.

- ^ Desio (1955b), p. 262.

- ^ Sale (2011), pp. 103–105.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), p. 220.

- ^ Himalaya Masala (28 September 2013). "K2 – Abruzzi Spur – 1954". Himalaya Masala. Archived from the original on 26 April 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ Desio (1955b), pp. 263–264.

- ^ Desio (1955a), p. 6.

- ^ Sale (2011), pp. 104–105.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), pp. 189–191.

- ^ Desio (1955b), pp. 263–264, 267, 268.

- ^ Desio (1955b), pp. 263, 265.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), p. 195.

- ^ Desio (1954).

- ^ Desio (1956).

- ^ Marshall (2009), pp. 143–154.

- ^ Marshall (2009), pp. 145–146.

- ^ Maraini et al. (2007).

- ^ Marshall (2009), pp. 155–174.

- ^ Desio (1955b), p. 265.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), p. 196.

- ^ a b Desio (1955b), pp. 266–267.

- ^ Desio (1955a), p. 5.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), pp. 198–201.

- ^ a b c d Isserman & Weaver (2008), p. 315.

- ^ Desio (1955a), pp. 9–10.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), p. 314.

- ^ Desio (1956), p. 128.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), p. 48.

- ^ Desio (1956), p. 150.

- ^ a b Desio (1955b), p. 267.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), p. 82.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), p. 203.

- ^ Desio (1955a), p. 11.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), pp. 154, 203.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), p. 207.

- ^ Viesturs (2009), p. 203.

- ^ a b Desio (1955b), p. 268.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), p. 56.

- ^ Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 78–79.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), p. 156.

- ^ Desio (1956), p. 168.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), pp. 175–176.

- ^ a b Maraini, Monticone & Zanzi (2004), p. 215.

- ^ Curran (1995), 1459/3989.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), p. 211.

- ^ Marshall (2009), pp. 169–170, 214–215.

- ^ Bonatti (2010), p. 108.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), p. 213.

- ^ Maraini, Monticone & Zanzi (2004), p. 213.

- ^ Marshall (2009), pp. 170, 212, 214.

- ^ Mantovani (2007), pp. 170–171.

- ^ Maraini, Monticone & Zanzi (2004), pp. 212–213.

- ^ Mantovani (2007), p. 173.

- ^ Kauffman & Putnam (1992), pp. 75–79.

- ^ Desio (1955b), pp. 267–268.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), pp. 202–207.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), pp. 207–209.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), p. 209.

- ^ Mantovani (2007), p. 169.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), pp. 212–213.

- ^ a b Mantovani (2007), pp. 169–170.

- ^ Isserman & Weaver (2008), p. 317.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), p. 214.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), pp. 216–217.

- ^ Mantovani (2007), p. 172.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), pp. 218–219.

- ^ a b c d Mantovani (2007), pp. 169–172.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), pp. 217–218.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), p. 221.

- ^ a b c d Mantovani (2007), pp. 173–174.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), pp. 221–222.

- ^ Desio (1956), pp. 194–196.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), pp. 222–225.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), p. 226.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), p. 228.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), pp. 228–229.

- ^ Desio (1955b), p. 270.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), pp. 229–230.

- ^ Conefrey (2015), pp. 231–236.

- ^ Viesturs (2009), p. 216.

- ^ a b Conefrey (2015), pp. 236–239.

- ^ a b Bonatti (2010), Editorial written by Marshall, pp. 10, 360–361.

- ^ Marshall (2009).

- ^ Conefrey (2015), chapters 11&12, pp. 233–271.

- ^ Curran (1995), 1813/3989.

Works cited

- Bonatti, Walter (2010) [1st pub. 2001]. Marshall, Robert (ed.). The Mountains of My Life (Google ebook). Translated by Marshall, Robert. UK: Penguin. ISBN 9780141192918. English translation of Montagne di una vita (Bonatti 1995)

- Conefrey, Mick (2001). Mountain Men: The Ghosts of K2 (television production). BBC/TLC. Event occurs at 43:00. Archived from the original on 14 February 2019. Retrieved 14 February 2019. The video is hosted on Vimeo at https://vimeo.com/54661540

- Conefrey, Mick (2015). The Ghosts of K2: the Epic Saga of the First Ascent. London: Oneworld. ISBN 978-1-78074-595-4.

- Curran, Jim (1995). "Chapter 9. A Sahib is About to Climb K2". K2: The Story Of The Savage Mountain (Kindle ebook). Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-1-444-77835-9.

- Desio, Ardito (1955a). "The 1954 Italian Expedition to the Karakoram and the Conquest of K2" (PDF). Alpine Journal. LX (290): 3–16.

- Desio, Ardito (1955b). "The Ascent of K2". The Geographical Journal. 121 (3): 261–272. Bibcode:1955GeogJ.121..261D. doi:10.2307/1790890. JSTOR 1790890.

- Desio, Ardito (1956) [1st pub 1955]. Victory over K2: Second Highest Peak in the World. Translated by Moore, David. McGraw Hill Book Company. English translation of La Conquista del K2 (Desio 1954)

- Houston, Charles (2005). Brotherhood of The Rope- K2 Expedition 1953 with Dr. Charles Houston (DVD/television production). Vermont: Channel 17/Town Meeting Television.

- Isserman, Maurice; Weaver, Stewart (2008). "Chapter 5. Himalayan Hey-Day". Fallen Giants: A History of Himalayan Mountaineering from the Age of Empire to the Age of Extremes (1 ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11501-7.

- Kauffman, Andrew J.; Putnam, William L. (1992). K2: The 1939 Tragedy. Seattle, WA: Mountaineers. ISBN 978-0-89886-323-9.

- Mantovani, Roberto (2007). K2 – A Final Report: Postscript. Translated into English in Marshall, Robert (2009). K2: Lies and Treachery. Carreg Press. pp. 166–174. ISBN 9780953863174.

- Maraini, Fosco; Monticone, Alberto; Zanzi, Luigi (2004). The Tre Saggi Report. Translated into English in Marshall, Robert (2009). "Appendix Two". K2: Lies and Treachery. Carreg Press. pp. 208–232. ISBN 9780953863174. Tre Saggi report

- Maraini, Fosco; Monticone, Alberto; Zanzi, Luigi; CAI (2007). K2 a Finished Story. Translated into English and summarized in Marshall, Robert (2009). "Chapter 7: Recognition". K2: Lies and Treachery. Carreg Press. pp. 155–180. ISBN 9780953863174. Club Alpino Italiano report

- Marshall, Robert (2009). K2: lies and treachery. Carreg Press. ISBN 9780953863174.

- Sale, Richard (2011). "Chapter 4. The First Ascent: The Italians, 1954". The Challenge of K2 a History of the Savage Mountain (EPUB ebook). Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-84468-702-2. page numbers from Aldiko Android app showing entire book as 305 pages.

- Viesturs, Ed (2009). "Chapter 6. The Price of Conquest". K2: Life and Death on the World's Most Dangerous Mountain (EPUB ebook). with Roberts, David. New York: Broadway. ISBN 978-0-7679-3261-5. page numbers from Aldiko Android app showing entire book as 284 pages.

- Vogel, Gregory M.; Aaronson, Reuben (2000). Quest For K2 Savage Mountain (television production). James McQuillan (producer). National Geographic Creative. Event occurs at 18:09. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

Italian sources and further reading

- Baldi, Marcello (1955). Italia K2 (motion picture) (in Italian). Mario Fantin (cinematographer). Club Alpino Italiano.

- Bonatti, Walter (1961). Le mie montagne [My Mountains] (in Italian). Zanichelli. Translated into English in On the Heights (Bonatti 1962)

- Bonatti, Walter (1962). On the Heights. Translated by Edwards., Lovett F. Hart-Davis. English translation of Le mie montagne (Bonatti 1961)

- Bonatti, Walter (1995). Montagne di una vita (in Italian). Baldini & Castoldi. Translated into English in The Mountains of My Life (Bonatti 2010)

- Desio, Ardito (1954). La Conquista del K2: Seconda Cima del Mondo [Victory over K2: Second Highest Peak in the World] (in Italian). Milan: Garzanti. Translated into English in Victory over K2 (Desio 1956)

- Horrell, Mark (21 October 2015). "Book review: The Ghosts of K2 by Mick Conefrey". Footsteps on the Mountain. Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- Lacedelli, Lino; Cenacchi, Giovanni (2006). K2: the price of conquest. Carreg. ISBN 9780953863136.

- Marshall, Robert (2005). "Re-writing the History of K2 – a story all'italiana" (PDF). Alpine Journal: 193–200.