1901 Constitution of Cuba

|

|---|

|

|

The 1901 Constitution of Cuba took effect in Cuba on 20 May 1902, and governments operated under it until it was replaced by the 1940 Constitution of Cuba. It was adopted by delegates to a Constitutional Convention in February 1901, but the United States, then exercising military authority over Cuba following the end of Cuba's war for independence from Spain, withheld its approval until the Convention amended the Constitution in June to incorporate language from a U.S. statute, the Platt Amendment, that placed limitations on Cuban sovereignty and provided a legal basis for future U.S. military interventions in Cuba.

Constitutional Convention

General Leonard Wood, the U.S. military governor of Cuba, called for a constitutional convention to meet in September 1900.[1] It met for the first time on 5 November 1900, in Havana. Wood opened the meeting by charging its thirty-one delegates with writing a constitution and formulating the future relationship between the U.S. and Cuba.[2] Domingo Méndez Capote presided and Enrique Villuendas and Alfredo Zayas served as secretaries.[citation needed]

The convention's central committee produced a first draft of the constitution in January, and it failed to mention the United States.[3] In early February the U.S. government expressed its displeasure at the Convention's failure to address the question of Cuban-American relations and its presumption that elections would occur 90 days after the constitution is adopted without giving any consideration, in the words of The New York Times, "as to whether the United States will be satisfied" with the document. A spokesman for the McKinley administration said:[1]

...that if Cuba manifests any unwillingness to accept the advice of the Administration, and demands a stronger expression of the will of the United States, still its military ruler, the President will ask the [U.S.] Congress to assemble for the purpose of sharing with him the task of impressing Cuba with the conviction in the United States that the right of free government is to be exercised there [in Cuba] only after this country has been assured that Cuba will be restrained by pledges that it is our duty to exact and should be the pleasure of Cuba to extend, without hesitation and in her own best interest.

The convention approved the text of the constitution on 21 February 1901, without adopting the language the U.S. government was insisting on. Modeled on the U.S. Constitution (1789), it divided the government into three branches:

- The bicameral legislature made up of a Senate and House of Representatives

- The judicial branch with a relative independence, but dependent on the executive and sometimes the legislature in terms of their appointments

- The executive branch, which concentrated great power under its control

The constitution was not submitted to a popular vote. Some in the United States had objected that the document should be subject to popular ratification, both to remove any question that the United States had imposed it by manipulating the Convention delegates and also as a matter of principle: "it is the privilege of the people to adopt or reject it; and it will not be securely ordained and established until it has been so adopted by the people".[4] Wood, however, had charged the Convention with writing and "adopting" a constitution. The Convention did that and, without holding a plebiscite, proceeded to establish procedures for elections to fill the offices established by the Constitution.

U.S. demands

The Platt Amendment was a U.S. statute that authorized the U.S. president to withdraw troops from Cuba following the Spanish–American War once he secured several specific promises from Cuba by treaty. Five provisions set restrictions on Cuban sovereignty and governed relations between the U.S. and Cuba. A sixth declared sovereignty over the Isle of Pines off the coast of the island of Cuba a question to be settled by a later treaty. A seventh guaranteed the U.S. the right to lease land in Cuba to establish naval bases and coaling stations. An eighth required the earlier seven provisions to be agreed to by treaty.

The U.S. government attempted to win the adoption of the Platt Amendment's terms by the delegates of the Cuban Constitutional Convention by promising to guarantee Cuban sugar producers access to the U.S. market. The delegates repeatedly rejected the text or sought to find acceptable language to substitute.[5] Wood negotiated with a committee tasked with crafting a text.[6] When they adopted a constitution in February 1901 they failed to include any version of it.[7]

The delegates tried to meet the U.S. demand by issuing an "opinion" on relations with the U.S., but remained in session anticipating it would not be sufficient. As of early April, in one observer's view, the delegates were divided between "nationalist sentiment" and the "sober judgment" that advised meeting the U.S. demands, and "they continue to beat about the bush for some deliverance from their dilemma, all the time ... drifting slowly but sensible toward an acceptance of the terms of the Platt Amendment."[8] A divided committee of delegates produced two more competing drafts in May.[9] As late as 1 June 1901, the Convention adopted language that Wood warned would not be acceptable, and U.S. Secretary of State Elihu Root confirmed that rejection.[10]

The delegates finally yielded to American pressure and ratified the Platt Amendment's provisions, first by accepting the report of its drafting committee on a 15 to 14 vote on 28 May,[11] and then as an amendment to the constitution by a vote of 16 to 11 on 12 June 1901.[12]

The United States transferred "government and control" to the government newly elected under the terms of the amended 1901 constitution on 20 May 1902.[13]

Cuba removed the Platt Amendment provisions from its constitution on 29 May 1934, as part of a new understanding of relations with the United States under the Good Neighbor policy of the administration of Franklin Roosevelt. At the same time, Cuba and the U.S. replaced their 1903 Treaty of Relations that had committed both countries to the Platt Amendment's requirements. Their new 1934 Treaty of Relations preserved only two elements of the earlier pact:

- the legality of actions taken by the U.S. in Cuba during its military occupation at the end of the Spanish–American War

- the lease continued unchanged.

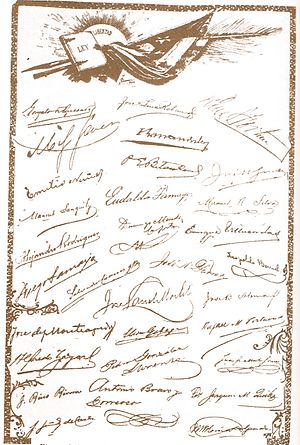

Delegates to the Constitutional Convention

The delegates to the Constitutional Convention that created the 1901 Constitution were:

- Domingo Méndez Capote (President)

- Enrique Villuendas (Secretary)

- Alfredo Zayas (Secretary)

- Leopoldo Berriel

- Pedro Betancourt

- Antonio Bravo Correso

- Francisco Carrillo Morales

- José N. Ferrer

- Luis Fortún

- Eliseo Giberga

- José Miguel Gómez

- Juan Gualberto Gómez

- José de Jesús Monteagudo

- Martín Morúa Delgado

- Emilio Núñez

- Gonzalo de Quesada y Aróstegui

- Joaquín Quilez

- Miguel Rincón

- Juan Rius Rivera

- José Luis Robau

- Alejandro Rodríguez Velazco

- Diego Tamayo

- Eudaldo Tamayo

See also

References

- ^ a b "Our Relations with Cuba" (PDF). The New York Times. 8 February 1901. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ "The Cuban Convention" (PDF). The New York Times. 6 November 1900. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ "The Cuban Constitution" (PDF). The New York Times. 26 January 1901. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- ^ "The Constitution of Cuba" (PDF). The New York Times. 6 August 1900. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- ^ "Constitution About Ready" (PDF). The New York Times. 14 February 2016. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ "United States and Cuba" (PDF). The New York Times. 16 February 1901. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ "Extra Session to be Held" (PDF). The New York Times. 23 February 1901. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ "The Situation in Cuba" (PDF). The New York Times. 8 April 1901. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ "Cubans' Reports on Future Relations" (PDF). The New York Times. 20 May 1901. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ "The Cubans Were Warned" (PDF). The New York Times. 2 June 1901. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ "Accept Platt Amendment" (PDF). The New York Times. 29 May 1901. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ "The Platt Amendment is Accepted by Cuba" (PDF). The New York Times. 13 June 1901. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ "Natal Day of the Republic of Cuba" (PDF). The New York Times. 21 May 1902. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- Marquez Sterling, Carlos & Manuel; Historia de la Isla de Cuba; Books & Mas, Inc., Miami, Florida (1996).

- The Platt Amendmment, the National Archives Online