185th Rifle Division

| 185th Rifle Division (September 1939 - March 11, 1941) 185th Motorized Division (March 11, 1941 – August 25, 1941) 185th Rifle Division (August 25, 1941 – 1947) | |

|---|---|

| Active | 1939–1947 |

| Country | |

| Branch | Red Army Soviet Army |

| Type | Infantry, Motorized Infantry |

| Size | Division |

| Engagements | Soviet occupation of the Baltic states (1940) Operation Barbarossa Leningrad strategic defensive Battle of Moscow Battles of Rzhev Operation "Seydlitz" Operation Mars Battle of Nevel (1943) Operation Bagration Lublin–Brest offensive Vistula–Oder offensive Operation Solstice East Pomeranian offensive Battle of Berlin |

| Decorations | |

| Battle honours | Pankratovo Praga |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Maj. Gen. Pyotr Lukich Rudchuk Lt. Col. Konstantin Nikolaevich Vindushev Maj. Gen. Mikhail Fyodorovich Andriushchenko Col. Sergei Ivanovich Aksyonov Col. Zenovii Samoilovich Shekhtman Col. Mikhail Maksimovich Muzykin |

The 185th Rifle Division was formed as an infantry division of the Red Army just as the Second World War had begun in the Oryol Military District, based on the pre-September 13, 1939 shtat (table of organization and equipment). As a standard rifle division, it took part in the Soviet occupation of Lithuania in June 1940. In early 1941, it was selected for conversion to a motorized infantry division, but in fact, it had received little in the way of vehicles by the start of the German invasion and so was a rifle division in all but name. It was sent to join Northwestern Front in the Baltic states with its 21st Mechanized Corps, and was soon assigned to 27th Army. Under these commands the division retreated through July and August as the German 16th Army advanced behind in the general direction of Novgorod. On August 25 it was officially reorganized as a regular rifle division.

During September it was substantially rebuilt with a large influx of conscripts. When the Army Group Center launched Operation Typhoon in the first days of October the division was forced to retreat into the Valdai Hills, where it became part of Vatutin's Operational Group and within days Kalinin Front. Later that month it took part on the fighting along the Kalinin–Torzhok road, especially in the Mednoye area, in which a large part of XXXXI Panzer Corps was encircled and forced to break out, at considerable cost. In the last stages of the German offensive on Moscow in November it was on the right flank of 30th Army on the north bank of the Volga River and then went over to the counteroffensive on December 6, driving south to recapture Klin, which happened on December 15. As the counteroffensive expanded the 185th was pulled into fighting for the town of Rzhev as part of 29th, 39th, and later 22nd Armies. It was badly damaged in a German counterattack in July 1942, and in November/December took part in an abortive advance up the valley of the Luchesa River. After rebuilding during early 1943, elements of the division staged a successful operation for a German strongpoint in August, earning the 185th its first battle honor. It was then reassigned, first to 3rd Shock and later 6th Guards Army, and played a relatively small part in the October - December battles near Nevel. It was removed from the front lines in early 1944 and railed south to join the 77th Rifle Corps of 47th Army in 1st Belorussian Front, where it remained into the postwar. In the concluding phase of Operation Bagration it earned a second honorific during the fighting near Warsaw. At the start of the Vistula-Oder Offensive in January 1945 the 47th Army initially played a secondary role, but despite this three of the 185th's regiments soon won battle honors of their own, and for taking Schneidemühl two regiments received decorations. Following the battles in Pomerania in February and March the division as a whole was awarded the Order of Suvorov. During the battle for Berlin the division attacked from the bridgehead over the Oder River at Küstrin and along with its Army helped lead the northern prong of the Soviet forces that encircled the city on April 25. It ended the war west of Berlin. During the rest of the year the division was part of the Group of Soviet Forces in Germany, but in early 1946 47th Army was disbanded and its units were withdrawn to the Soviet Union. In 1947 the 185th's remaining personnel were used to create a rifle brigade in the Ural Military District.

Formation

The division was formed at Belgorod in the Oryol Military District in September 1939. It was based on the 163rd Rifle Regiment of the 55th Rifle Division. In June 1940 it was moved to the Byelorussian Military District and from there it took part in the Soviet occupation of Lithuania beginning on June 15. In early 1941 it was pulled back to the Moscow Military District to be reorganized.[1]

185th Motorized Division

The division began reforming on March 11, as part of the prewar buildup of Soviet mechanized forces, at Idritsa, as part of the 21st Mechanized Corps.[2] Its order of battle was as follows:

- 280th Motorized Rifle Regiment

- 415th Motorized Rifle Regiment

- 660th Motorized Rifle Regiment

- 124th Tank Regiment

- 470th Artillery Regiment

- 49th Antitank Battalion

- 13th Antiaircraft Battalion

- 125th Reconnaissance Battalion

- 340th Light Engineer Battalion

- 194th Signal Battalion

- 155th Medical/Sanitation Battalion

- 22nd Motor Transport Battalion

- 148th Repair and Restoration Battalion

- 64th Division Artillery Workshop

- 118th Field Repair Shop

- 100th Motorized Field Bakery

- 364th Field Postal Station

- 505th Field Office of the State Bank

Maj. Gen. Pyotr Lukich Rudchuk moved up from deputy commander of the division to full commander on the day the conversion began. It had an unusual composition for a Soviet motorized division with three motorized rifle regiments instead of the usual two, as it was formed from a full division. 21st Mechanized (42nd and 46th Tank Divisions, 185th Motorized, and 11th Motorcycle Regiment) was in the Reserve of the Supreme High Command on June 22.[3] In reality, the Corps had no tanks at all, and trucks were in very short supply, so most of the riflemen were on foot. The 185th had 90 percent of its assigned personnel, but 75 percent of them had been received from April to June, leaving very little time for unit or individual training.[4]

By the beginning of July the 21st Mechanized Corps had been moved to the reserves of Northwestern Front. It was soon assigned to 27th Army.[5] When Barbarossa began this Army was in Latvia, acting as a backup to the Front's main forces. Over the first 18 days of the invasion the Front's forces had to retreat as far as 600km in the face of Army Group North's attack, with 27th Army withdrawing in the direction of Kholm, being slowly pursued by II Army Corps, which captured the town in early August. On August 12 the Front's 11th and 34th Armies scored a short-lived success at Staraya Russa, but once this was reversed the Front pulled back across the Lovat River.[6]

General Rudchuk left his command on August 18; he served in command of several reserve cavalry regiments and brigades for the duration of the war. Lt. Col. Konstantin Nikolaevich Vindushev took over command of what remained of the 185th, and on August 25 reality was acknowledged when the division was officially reformed as a regular rifle division.[7]

Reformation

Once reformed as a rifle division the 185th's order of battle became as follows:

- 257th Rifle Regiment

- 280th Rifle Regiment (from 280th Motorized Rifle Regiment)

- 1319th Rifle Regiment (from reservists)

- 695th Artillery Regiment[8]

- 49th Antitank Battalion

- 125th Reconnaissance Company (later 158th Reconnaissance Battalion)

- 340th Sapper Battalion

- 194th Signal Battalion (later 586th Signal Company)

- 155th Medical/Sanitation Battalion

- 98th Chemical Defense (Anti-gas) Company

- 22nd Motor Transport Battalion (until October 2, 1941)

- 22nd Motor Transport Company (until September 10, 1942)

- 269th Motor Transport Company (until June 25, 1943)

- 268th Motor Transport Company

- 335th Field Bakery

- 1031st Divisional Veterinary Hospital

- 364th Field Postal Station

- 505th Field Office of the State Bank

Lt. Colonel Vindushev remained in command. On the same day, Army Group North's 18th Army resumed its advance on Leningrad, which was encircled on September 8. Later in the month the Novgorod Operational Group, under Northwestern Front command, was formed, and by October 1 it consisted of the 185th, 180th, and 305th Rifle Divisions, plus the 3rd Tank Division, which had no tanks and was converting to infantry. The Group was defending a 30km sector along the Volkhov River from Dubrovka to Lake Ilmen.[9]

Battle for Kalinin

Army Group Center launched its Operation Typhoon on September 30 in an attempt to capture Moscow before winter. This offensive was an immediate success, with four Soviet armies encircled and largely destroyed by October 10 in the Vyazma area. With their flanks exposed the armies on each side were forced to fall back. Lt. Gen. N. F. Vatutin, the chief of staff of Northwestern Front, was ordered to organize a force to defend the city of Kalinin. Vatutin's Operational Group would consist of the 183rd and 185th Rifle Divisions, the 46th and 54th Cavalry Divisions, the 8th Tank Brigade, 46th Motorcycle Regiment, and an unnumbered Guards Mortar battalion.[10]

During the period since its reformation the 185th had been relatively disengaged from the fighting, and had also received a considerable influx of replacements, so that it now had a strength of 12,046 personnel, armed with 196 automatic weapons, 17 mortars of all calibres, 32 regimental and divisional guns, but just one antitank gun. Despite this latter shortage, the division was unusually strong in numbers for this period of the war. However, most of these men were again poorly trained conscripts filling the ranks around a much smaller cadre of experienced soldiers. As a result, "its performance at Kalinin can only be termed lacklustre." Vatutin directed the division to complete concentration in the area of Svyatsevo, B. Petrovo, and Budovo on the morning of October 17. STAVKA Directive No. 003053, dated 1830 hours the same day, established Kalinin Front, under command of Col. Gen. I. S. Konev, consisting of 22nd, 29th, and 30th Armies plus Vatutin's Operational Group, which now also included the 246th Rifle Division.[11]

The city of Kalinin had fallen to the 1st Panzer Division of XXXXI Panzer Corps on October 14. On the same day the 8th Tank Brigade, commanded by Col. P. A. Rotmistrov, was racing toward Vyshny Volochyok and Torzhok from Valdai, with the 183rd and 185th Divisions, and the two cavalry divisions, in its wake. The following day the panzers, along with the 900th Lehr Brigade, began crossing the bridge they had seized over the Volga, as the first stage of a grandiose plan to link up with Army Group North through the Valdai Hills, which would encircle Northwestern Front. This plan not only disregarded the continuing resistance of Red Army forces, but also the state of the roads and the logistical shoestring the German forces were operating on. The latter was worsened when the 21st Tank Brigade launched a surprise raid on the supply lines south of the city on October 17.[12]

At 0600 hours the same day, 1st Panzer and 900th Lehr began their drive up the Kalinin–Torzhok road and made steady progress through the morning. At noon the headquarters of XXXXI Corps recorded that there was a possibility of capturing the bridge at Mednoye, crossing the Tvertsa River about 28km from Kalinin and nearly halfway to Torzhok. In the event, not only was this objective taken but the panzer column pressed on to the village of Marino, 14km farther along. Only a depleted tank regiment of 8th Tank Brigade was providing any resistance before being withdrawn to the northeast, uncovering the road. Once he learned of this, Konev "hit the ceiling" and demanded Rotmistrov's arrest for cowardice. Vatutin chose to send Rotmistrov a blistering order, stating:

Immediately, without losing a single hour, return from Likhoslavl, and with parts of 185th Rifle Division, rapidly strike at Mednoye to destroy the group of enemy that have broken through and seize Mednoye. It is time to finish with the cowardice!

Later in the day, Maj. Dr. J. Eckinger, the commander of 1st Panzer's advance detachment, was killed while leading his troops in an effort to outflank Rotmistrov's tanks. This death symbolically marked the end of the advance on Torzhok.[13]

Battle for the Torzhok Road

By the evening the forces that the Soviet command had envisioned to reverse this German advance were moving into place. The 183rd Division had already moved through Torzhok, and its leading elements were fighting in the Marino area. Lt. Colonel Vindushev had led his men to positions about 16km north of Mednoye, with the two cavalry divisions ahead of them. Altogether, Vatutin's Group consisted of about 20,000 men (of which the 185th made up more than half), 200 guns and mortars, and twenty operational tanks. Its opponents had far fewer men, strung out over 54km of road, low on fuel and ammunition, and partly encircled. Vatutin gave orders for a general attack at dawn on October 18; the 185th and 8th Tanks would make a joint attack due south toward Mednoye. Although the 133rd Rifle Division's attack northeast of Kalinin cut the road at its base early on, the 185th was late in reaching its jumping-off positions and the 8th Tanks was still reorganizing near Likhoslavl. On the same day Vatutin's Group came under command of 31st Army. In his evening report to STAVKA, Konev stated that the 185th was "marching on Torzhok"; this was flatly false, as were many other statements in this document.[14]

By 0800 hours on October 19 the XXXXI Corps reported that the situation of 1st Panzer was "critical"; it and 900th Lehr would be forced to abandon Marino. At Mednoye, one Soviet account states that the 1319th Rifle Regiment, supported by a tank regiment of 8th Tanks, made use of the cover of fog to attack from woods north of the town, taking the defenders by surprise. Despite bombing by the Luftwaffe after the weather cleared, Mednoye was taken by 1400 hours, releasing 500 Red Army men who had been captured. However, Vatutin's orders to Vindushev are somewhat contradictory:

185th Rifle Division and 8th Tank Brigade will forced march by dawn 19.10 to get to the area of Likhoslavl, Ilinskoye, Ivantsevo, from there make a rapid strike on Mednoye, the objective, working closely with 183rd Rifle Division, to destroy the enemy west of Mednoye not allowing him to withdraw from the attack of 183rd Rifle Division to the east. Going further, building on the success, by the end of the day take Poddubke.

Given that the distance from Likhoslavl to Mednoye is 19km, it's doubtful that any attack was made at dawn. None of this can be reconciled with the records of 1st Panzer, which state: "Also on the evening of 19 October, the division does not want to give up Mjednoje [Mednoye] yet, since the enemy is not active there, and reconnaissance reports the area 5-8km around as free of the enemy."[15]

Before dawn on October 20 the 1st Motorcycle Battalion of 1st Panzer was attacked from north and south, taking heavy losses in both machines and men. The northern prong was the 185th with 8th Tanks, finally pushing into Mednoye and linking up with 243rd Rifle Division attacking from the south. This action cut off 900th Lehr, which was withdrawing from Marino, from 1st Panzer. The brigade was directed to attempt a "do or die" breakout from Mednoye through the area between the Torzhok road and the Tma River, all with minimal fuel and ammunition. The spearhead of 1st Panzer was reporting that it was no longer able to attack and would require rest before it could break out of encirclement. Its path back to Kalinin was blocked mainly by the 133rd Division.[16]

Overnight, Vatutin prepared his final orders to his Group. These orders, which may have never actually been issued, called for the 185th and 8th Tanks to finish off all German forces in the Mednoye area before advancing across the Volga all the way to the western tip of the Moscow Sea. This was part of an impractical plan intended to fulfil Konev's earlier "large solution" of encircling all of XXXXI Corps. That these orders were probably not issued is reflected in the fact that shortly after the 185th was moved to 30th Army without the 8th Tanks. This Army's next task was to retake Kalinin itself with attacks from the northeast, north and southeast. During October 21 some remnants of 1st Panzer managed to escape the pocket, after destroying all their vehicles except the tanks, and the pocketed forces were within 3km of Kalinin, being supported by shuttle flights of Ju 87 dive bombers to keep the Soviet forces at bay. Despite this support the breakout attempt was put off to the next day.[17]

According to a postwar Soviet history of the fighting on the Kalinin axis:

By 21 October, 8th Tank Brigade, the Separate Motorized Rifle Brigade, 185th and 133rd Rifle Divisions and also three divisions of 29th Army had inflicted a serious defeat on the enemy group in the area of Marino-Mednoye. A significant part of this group was exterminated. So, for example, just in the woods near Gorodnya village our armies destroyed over 500 enemy soldiers and officers, some tens of motor vehicles, twenty tanks and over 200 motorcycles were captured. Only for elements of the enemy group was it possible to break through to Kalinin.

German sources state that from October 13 to 18 the 1st Panzer and 900th Lehr suffered a total of 457 casualties, while over the next two days 1st Panzer alone lost an additional 501 men; the 900th also took substantial losses during the latter period. The battle for the Torzhok road would mark the first permanent liberation of Soviet territory during the war. On October 27 the forces of Army Group North that were intending to meet up with XXXXI Corps to encircle Northwestern Front were compelled to withdraw across the Volkhov.[18]

Counterattack on Kalinin

Konev took October 22 to reorganize his forces prior to launching an offensive to retake Kalinin. As part of this effort his orders included:

30th Army, with 5th, 185th and 256th Rifle Divisions and 21st Tank Brigade, was to attack Kalinin from the northeast, east and south and, by the end of 23 October, to clear the northeastern and southern sectors of the city, while preventing any enemy from retreating to the south.

In the event the 185th would not take part in this attack. German 9th Army had taken the town of Rzhev on October 14 and since then had been slowly advancing north against 22nd Army. This put pressure on Konev's right flank and could have led to the loss of Torzhok from another direction. To begin with he moved the 183rd Division and the Separate Motorized Rifle Brigade to backstop 22nd Army. It appears that Konev was unsure if this was an adequate precaution and hedged his bets by retaining the 185th as a Front asset. It was still by far the strongest division he had available, and 30th Army would have no real chance to retake Kalinin without it. Vindushev was ordered to "establish a defensive line by the morning of 24 October" with positions 12-20km northeast of the city, on each side of the road to Bezhetsk. Konev initially detached the 257th Rifle Regiment to reinforce the severely depleted 5th Division, but within days the plan to retake the city was put on hold, in the event for another two months.[19] By the beginning of November the 257th was under direct command of the Front, but during the month it returned to Vindushev's control.[20]

Battle of Moscow

On November 15 Army Group Center renewed its Moscow offensive. At this time 30th Army (5th and 185th Divisions, 107th Motorized Rifle Division, 46th Cavalry, 8th and 21st Tanks, and other units, a total of about 23,000 men) was defending a line from Malye Peremerki (6km southeast of Kalinin) to Slygino to Tsvetkovo to Dorono and then along the east bank of the Lama River. The 185th, which had been serving as Kalinin Front's reserve, remained in reserve positions near Zhornovka, 6km north of Kalinin. During the night of November 15/16 Vindushev was ordered to move to the Zavidovo area to become the 30th Army reserve; this movement continued through November 17. Over the first three days German forces attacked all along the Army's front, with the main effort south of the Moscow Sea, where the boundary with Kalinin Front was located. For this reason, the Army was transferred to Western Front at 2300 hours on November 17. The 3rd and 4th Panzer Armies intended to encircle Moscow from the north by attacking in the Klin–Solnechnogorsk and Istra directions.[21]

The next day German mobile troops advancing on the Zavidovo axis ran into tough resistance attempting to reach the road to Klin. The 185th was holding a sector about 15km wide from Sverdlovo to Vidogoshch, north of on the left bank of the Volga. In the first five days of the offensive the German mobile forces had advanced 15-25km and had failed to achieve a breakthrough. The offensive continued on November 21 with one group, consisting of 6th Panzer and 14th Motorized Divisions, attacking from about 10km southeast of Zavidovo. By the end of the next day Klin had been half encircled, and this was completed on November 23, with the town falling soon after. By the next day, while a wedge had been forced between 30th Army and 16th Army to its south and gains had been made toward Moscow, the Soviet front had bent but not broken. By the morning of November 28 the right flank forces of 30th Army, including the 185th, were continuing to hold their positions on the left bank of the Volga, throwing back all German efforts to infiltrate the lines. Over the next two days the division continued to improve its positions while German activity was minimal. During December 2-5 the German forces facing 30th Army went over to the defense, guarding the flank of their groups still trying to reach Moscow.[22]

Moscow Counteroffensive

During the last days of the German offensive the 20th and 1st Shock Armies arrived on the right flank of Western Front to backstop the 30th and 16th; 30th Army was also reinforced with three fresh divisions. It went over to the counteroffensive on December 6. While it attacked across its entire front the main thrust was against Klin, with a secondary thrust on Rogachevo; these did not involve the 185th. Under this pressure German forces began a partial withdrawal on Klin and Solnechnogorsk. During December 8 the 185th, with the 379th Rifle and 82nd Cavalry Divisions, engaged the 36th Motorized Division along a line from Shetakovo to Minino to Berezino. This line had been extensively fortified and slow progress was made slower when the 185th came under air attack.[23]

On December 7, Politruk Nikolai Pavlovich Bocharov had led an action which would make him a Hero of the Soviet Union. He was serving as the political officer of a company of the 280th Rifle Regiment. He led the company through a gap he had found in the German lines near the village of Arkhangelskoye, which resulted in the capture of two German guns, including a 37mm antitank gun. He took the gun layer's position to eliminate the crews of two more German guns, and then began firing on their infantry with up to 100 rounds, killing or wounding many and forcing the remainder to retreat. The company captured 11 machine guns, plus other firearms, mines, and several vehicles. He would receive his Gold Star on January 12, 1942. Bocharov continued to serve as a political officer under several commands for the duration of the war, and postwar he continued his military education, moving to the armored forces, taking command of the 8th Guards Tank Division in November 1957. He was moved to the reserve in February 1976, and died in Kyiv on September 27, 1997.[24]

From December 9-11, 30th Army's right flank forces fought intensive battles with 36th Motorized and the 86th Infantry Division. It was not until the 11th that the 185th was able to force the 36th from Varakseno and Arkhangelskoe. The following day the Army attacked along both of its flanks. By 1300 hours the division had liberated Bezborodovo, Mokshino and Kabanovo while continuing to advance toward Novozavidovsky. At the end of the day the Army had Klin half-encircled. The 185th attacked along the south shore of the Moscow Sea on December 12, capturing several objectives while pursuing the defeated German troops ahead of them. By the end of December 14 and the following night the division, along with the 379th and a mobile group that the Army had formed, continued to constrict the German Klin grouping, reaching a line 12km northwest of Vysokovsk. However, 1st Shock was unable to overcome German resistance and complete the encirclement. Most of the German grouping were old opponents of the 185th, including 1st Panzer, 900th Lehr, and 36th Motorized, totalling about 18,000 combat troops and 150 tanks. At 0200 on December 15 units of 30th Army's 371st Rifle Division entered the town. Prisoners were taken and substantial equipment captured, but the remains of the garrison were able to filter into Vysokovsk under pursuit.[25]

30th Army returned to Kalinin Front at 1200 hours on December 16, the same day the city was liberated. The Army was to capture Staritsa with its left wing while the right wing blocked the retreat of the 9th Army's forces from Kalinin.[26]

Battles for Rzhev

The first Rzhev-Vyazma offensive began on January 8, 1942, based on a directive from the STAVKA of the previous day, which stated the objective "to encircle, and then capture or destroy the enemy's entire Mozhaysk–Gzhatsk–Viaz'ma grouping". Kalinin Front's right wing would attack from northwest of Rzhev toward Sychyovka and Vyazma. Within days the forces of 29th Army were moving to encircle Rzhev from the west, reaching as close as 8km to the city by January 11. The STAVKA ordered General Konev that it be taken the following day, but despite reinforcements the effort fell short.[27] Later in the month the 185th was transferred to this Army.[28]

On January 21–22 the German forces southwest and west of Vyazma went over to the attack. The immediate aim was to free the German troops encircled in the Olenino area and the close the gap through which supplies were flowing to 29th and 39th Armies and the 11th Cavalry Corps. The gap was closed on January 23 and the two armies now had only a narrow corridor between Nelidovo and Bely for communications with the Front. Realizing the danger of the situation Konev ordered 30th Army westward to attempt to reopen the gap. However, further German attacks on February 5 broke communications between 39th and 29th Armies and the latter was now completely encircled. 30th Army made repeated efforts to break through the German defenses near Nozhkino and Kokoshkino; at times only 3–4km remained to reach the encircled units, which were striving to break out to the north. By mid-month Konev had ordered the 29th Army commander, Maj. Gen. V. I. Shvetsov, "to withdraw in the general direction of Stupino", to the southwest toward 39th Army. He was further ordered "to bring out the troops in an organized fashion; if it is impossible to bring out the artillery, heavy machine guns and mortars, to bury such equipment in the woods." The units of 29th Army began to trickle out of encirclement to link up with 39th Army on the night of February 17 and continued for the next several days. By February 28 5,200 men had come out of the pocket, 800 of which were wounded. The Army's losses between January 16 and February 28 amounted to 14,000 men.[29]

During February 19-22 the remnants of the 185th concentrated southwest of the village of Praseki; it had only 1,743 men still on strength. Among the casualties was Lt. Colonel Vindushev, who was wounded and evacuated. He returned to the front on May 21 as commander of the 27th Guards Rifle Division, and then served as commander of seven different brigades and divisions as a colonel before ending the war leading the 106th Guards Rifle Division and being promoted to the rank of major general on April 20, 1945. After the war he joined the tank and mechanized forces, and retired in April 1956. He was replaced by Lt. Col. Stanislav Gilyarovich Poplavsky. This Polish officer would end the war as a major general in command of the First Polish Army. On March 11 he was in turn replaced by Maj. Gen. Sergei Georgievich Goryachev, who was concurrently in command of the 256th Rifle Division.

Operation Seydlitz

In March the 185th was assigned to 39th Army.[30] During the following months the Army held its positions, always under severe supply constraints, especially during the spring rasputitsa. General Goryachev left the division on May 6 to attend the Voroshilov Academy. He was replaced by Col. Mikhail Fyodorovich Andriushchenko, who had been serving as chief of staff of the 256th. This officer would be promoted to the rank of major general on February 4, 1943.

In May and June, Army Group Center began planning a limited offensive to eliminate the smaller Soviet salients to its rear. By this time the 185th had been transferred to 22nd Army, still in Kalinin Front.[31] Operation Seydlitz began on July 2, and faced heavy resistance, but by July 5 the commander of 39th Army, Lt. Gen. I. I. Maslennikov, had decided to withdraw from the salient. On July 9, the escape corridor was more-or-less sealed, and several subunits of the 185th had become encircled again. Beginning on July 15, those elements of the division outside the encirclement probed the German lines to make contact at points where a breakout could be possible. On July 18, Andriushchenko sent a reconnaissance force through the German lines to link up with 39th Army headquarters. This was now under Lt. Gen. I. A. Bogdanov, as Maslennikov had been wounded. In the course of the day all the scattered and disorganized units of in the pocket were combined into a single regiment, which became part of the 256th Division. On July 20, Andriushchenko made another probing attack to assist Bogdanov. Bogdanov decided to make a sudden breakout attempt in coordination with units of 22nd and 41st Armies. Despite stubborn German resistance, by 2300 hours on July 21 3,500 had come out of the encirclement and by 0400 on July 22 more than 10,000 men. A report from 22nd Army stated:

People are emerging in an organized fashion. Men are collapsing from utter exhaustion and the lack of food. The bulk of those who have come out have gathered at an assembly point, [and there is] heavy movement in the corridor through the German lines. Most of the men are armed with rifles and submachine guns.

During July, 39th Army recorded 23,647 total personnel losses, including 22,749 missing-in-action; this may or may not have included the pocketed units of the 185th.[32]

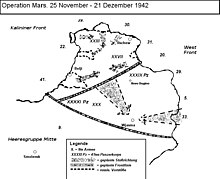

Operation Mars

At the start of the November offensive 22nd Army was under command of Lt. Gen. V. A. Yushkevich and consisted of about 80,000 personnel, as well as 270 tanks due to the presence of the 3rd Mechanized Corps. The Army faced relatively weak defenses along the valley of the Luchesa River held by the 216th Grenadier Regiment of the 86th Infantry Division of XXXXI Panzer Corps and the 252nd Grenadier Regiment of the 110th Infantry Division of XXIII Army Corps. Yushkevich's characteristic plan was to attack at the boundary between the two divisions while also staging a demonstration attack with his 362nd Rifle Division. The Army carried out an extensive regrouping prior to the start of the offensive, moving up the 3rd Mechanized while Colonel Andriushchenko concentrated his 280th and 1319th Rifle Regiments on a 2km-wide sector just south of the Luchesa, leaving the 257th to cover the remainder of the division's sector, which extended 15km to the north. The two regiments, flanked by the 238th Rifle Division to the south, were to attack early in the morning of November 25, penetrate the German defenses, and clear a passage for the mechanized forces to advance up the valley.[33]

The terrain facing the Army was formidable. The river was narrow and winding, flanked on both sides by heavy forests and frozen swamps. There was one improved track that followed the river and few tracks to follow through the forests. The nearest real road was that which linked Olenino to Bely, almost 20km from the front. The artillery preparation began at 0730 hours and shortly before 0900 the men of the 185th went into the attack. While the artillery had been effective in many places, the scattered nature of the German strongpoint defense made it impossible to eliminate every position. Thus, while some forward battalions made good progress, others were held up by fire from undestroyed German bunkers. Moreover, the tank support provided by 3rd Mechanized, which amounted to a tank company for each assaulting rifle battalion, was uneven due to the terrain and uncleared minefields. During the first hours the two regiments pushed through the forward defenses, but then came up on a number of fortified villages in open ground which slowed the advance. At noon the 1st Guards Tank Brigade came up to provide support, which allowed the 185th's regiments to gain another 1,000m, but a limited attack by the 257th north of the Luchesa made no progress at all. At dusk, Andriushchenko halted the assault, and made preparations to cross the river northward in the morning to seize the fortified town of Grivo.[34]

At dawn on the following day, after another artillery preparation, the assault was renewed. The 280th Regiment made an attack across the frozen Luchesa and obtained a foothold on the north bank. This success forced the defenders to leave their forward positions and withdraw in good order to Grivo. As the 280th approached it was met with heavy fire from small arms, machine guns, and mortars, while artillery fire blasted its ranks. 1st Guards Tanks struggled to cross the river and fell behind, and without their support the infantry assault faltered by noon. At the same time, the 1319th Regiment, backed by most of 1st Guards Tanks, penetrated the positions south of the river and began a slow advance on both sides of the "road" to Starukhi. This came to a halt halfway to the village when the regiment was struck by a heavy counterattack by newly-arrived German motorized infantry. The two sides traded territory through the rest of the day, while the tanks suffered heavy losses. Toward dusk the 1st Guards commander, Maj. Gen. M. Ye. Katukov, withdrew the brigade to regroup and recombine with the vehicles that had crossed the river. The fresh German troops turned out to be the 2nd Battalion of the Grenadier Regiment of Großdeutschland Motorized Division.[35]

Early on November 27 the 22nd Army finally began experiencing some success. The 280th resumed its attack on Grivo, now without tanks, but now the concentrated 1st Guards Tanks, joined by the 3rd Mechanized Brigade, forced aside the grenadiers along the Starukhi road with the help of the 1319th, eventually reaching the outskirts of the town which was also heavily defended. The 1319th now forced a small lodgement across the river south of Grivo. Meanwhile, the 238th Division pushed the German forces back into the village of Karskaya while 49th Tank Brigade raced into the open country south of Starukhi until they were halted north of Goncharovo by further German reinforcements. General Yushkevich believed that the penetration was finally occurring but by nightfall the advance had once again been halted by stiffening resistance.[36]

Kalinin Front expected a decisive attack on November 28 that would clear the Luchesa valley and drive to the Olenino–Bely road, but the arrival of Großdeutschland turned the battle into a two-day vicious slugfest. An overnight regrouping was hindered by driving snow, and the planned attack was delayed until noon. Early on November 29 both sides attacked virtually simultaneously. North of the river the two regiments of the 185th failed to take Grivo. Despite this setback the remaining forces of 22nd Army drove the defenders to the point of collapse, and the commanders of the two German corps set about scraping up every available reserve to contain the attack. On the other hand, Yushkevich had lost almost half of his original 270 tanks destroyed, and losses in the 185th and 238th were over 50 percent.[37]

Despite his misgivings, Yushkevich issued new orders in the early hours of December 1 to renew the attack at dawn in a staggered manner with all his forces following the strongest artillery preparation he could muster. By now the operation had clearly failed on other some other sectors but the overall commander of the operation, Army Gen. G. K. Zhukov, was determined to persist with any and all successes achieved to date. 1st Guards Tanks would lead the attack across the river in the direction of Vasiltsovo, with support from infantry of the 3rd Mechanized. The 1319th Regiment, with a battalion of 1st Mechanized Brigade, would advance on the left of the spearhead, and most of the rest of 3rd Mechanized Corps on its right. All movement was hampered by heavy new snowfall. In fighting whose intensity exceeded that of the previous days, 22nd Army made steady but bloody progress. The mixed infantry and armor force bashed its way out of the Luchesa valley, captured Travino, and drove the defenders to a new line running east from Grivo. The 257th Regiment joined the assault and made a small advance to the north of the 280th.[38]

Over the next two days Yushkevich stuck to his plan. On December 2 he committed his last reserves, a rifle brigade and a tank regiment to strengthen the forward formations. Andriushchenko was ordered to throw his entire division against the defenses north and east of Grivo. By dusk on December 3 this finally succeeded and the German battlegroup "Lindemann" abandoned the village, falling back to a shorter line 4km to the rear. This withdrawal gave Yushkevich a chance to move additional forces to his right flank, which was now within 2km of the Olenino road, but each time he extended this flank it came up against German reinforcements arriving in the nick of time. By now, 22nd Army was effectively burned out, with well under 100 tanks operational and infantry losses at 60 percent. Zhukov, however, was still demanding that the road be taken.[39]

Yushkevich planned to resume his attack at 0900 hours on December 7. However, before dawn on December 6 German motorized reinforcements began arriving along the highway. The counterattack that followed threw 22nd Army completely off balance and drove it back to 6km distance from the highway; most of the Army's sparse reserves were consumed in efforts to regain lost positions. Nevertheless, he was ordered to carry out his planned attack the next morning, which predictably failed. The efforts continued until December 11 when Zhukov called a halt. The 185th was pulled back on December 10 after suffering 4,189 killed and wounded. Yushkevich was removed from command on December 15, replaced by Maj. Gen. D. M. Seleznev. The next day this officer noted the movement of German reserves northward from Bely as the Red Army forces in that sector had been defeated. During the rest of the month German forces attempted to drive 22nd Army back to its starting positions, but this effort ended on January 1, 1943, with most of the Luchesa salient still in Soviet hands.[40]

Battle of Nevel

In a report by Lt. Gen. A. I. Antonov, the First Deputy Chief of the General Staff, dated January 4, the chief of staff of Kalinin Front was made aware of "shortcomings in the organization of the defense" in which the division was specifically noted:

... 4. Primarily only people in the rear units and facilities have been provided with warm items, while at the same time the soldiers and officers of the combat units have not received winter uniforms (the 185th, 238th and others).

5. Weapons, as a consequence of the lack of care in the combat units, are rusty, filthy, rifles lack foresights; many of the automatic weapons no longer fire automatically because of defects, and heavy machine guns are not operable (185th, 362nd, 238th Rifle Divisions and others).

It is necessary to take urgent measures to eliminate the shortcomings noted above. Report regarding the measures you have taken by 7 January 1943. -- Antonov[41]

In March the division returned to 39th Army, still in Kalinin Front, and in July it was assigned to the 83rd Rifle Corps in the same Army.[42] On August 13 the division carried out an independent operation which successfully liberated a German-held hamlet in the Palkinsky Raion and was soon awarded its name as a unique battle honor:

PANKRATOVO – ... part of the forces of 185th Rifle Division (Major General Andriushchenko, Mikhail Fyodorovich)... The troops that broke through the enemy’s heavily fortified zone and defeated his long-held strongholds of Pankratovo and others, by order of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief of 19 September 1943 and a commendation in Moscow, are given a salute of 12 artillery salvoes by 124 guns.[43]

On September 16 the division was withdrawn to the Reserve of the Supreme High Command and on October 1 it was reassigned to 3rd Shock Army, still in Kalinin Front (2nd Baltic Front as of October 20), under direct Army command.[44]

As of October 1 the 185th had a personnel strength of roughly 5,500 men, and was one of five rifle divisions in the Army. In the deployment for the Nevel operation the Army commander, Lt. Gen. K. N. Galitskii, concentrated most of his divisions and brigades on a 4km-wide penetration sector, supported by all 54 of the Army's tanks and 814 of its guns and mortars. On the other hand, the 185th was deployed to the north, astride the Velikiye Luki–Nevel road. Galitskii planned to precede his main attack with a reconnaissance-in-force beginning at 0500 hours on October 6. The Army faced the German XXXXIII Army Corps of three divisions, including the 83rd Infantry Division which it had defeated previously at Velikiye Luki, and part of II Luftwaffe Field Corps. The boundary between the two German corps also marked the boundary between Army Groups North and Center.[45]

The reconnaissance was followed by a 90-minute artillery preparation at 0840 hours and air attacks. The 2nd Luftwaffe Field Division was almost immediately routed. 54 vehicles of the 78th Tank Brigade carrying a regiment of the 21st Guards Rifle Division tore deep into the German positions and seized Nevel off the march by the end of the day following an advance of more than 20km. Despite this spectacular early success the German high command quickly assembled reserves to contain the advance while being unable to regain any lost ground. According to Soviet sources the Nevel operation ended on October 10 but local battles for position continued until October 18.[46]

Pustoshka Offensive

In an early morning fog on November 2 the 3rd and 4th Shock Armies penetrated the defenses of the left flank of 3rd Panzer Army southwest of Nevel. After the breakthrough, which opened a 16km-wide gap, 3rd Shock turned to the north behind the flank of German 16th Army while 4th Shock moved southwest behind 3rd Panzer Army.[47] 3rd Shock headed deep into the German rear area towards its objective, the town of Pustoshka on the Velikiye Luki-Riga railroad line. By November 7 the Army's lead elements had penetrated more than 30km deep on a 40km front. Army Group North faced an even more dire situation when 6th Guards Army entered the fighting on November 10 in the lake district northeast of Nevel. At about the same time the 185th was moved to the 97th Rifle Corps of this Army, which had been assigned the task of cutting through the long German-held salient that stretched from Novosokolniki nearly as far south as Nevel, although 97th Corps primarily provided protection of the right flank. This attack was repelled and on November 15 the 6th Guards Army was ordered over to the defense, followed by the remainder of 2nd Baltic Front on November 21.[48] On November 28, General Andriushchenko was moved to command the 28th Rifle Division, which had led the breakthrough to Nevel. He would go on to lead the 98th Rifle Corps and the 65th Guards Rifle Division before the end of the war. Col. Sergei Ivanovich Aksyonov took over command of the 185th; he had previously led the 119th Guards Rifle Division.

Redeployment to 1st Belorussian Front

2nd Baltic Front began a new offensive to eliminate the Novosokolniki–Nevel salient on the way to Idritsa on December 16. The attack made almost no headway against the fortified German lines, but by late on December 27 Hitler was convinced the salient was a "useless appendage" and its evacuation was finished by January 8, 1944.[49] In the follow-up to this the division was again reassigned by January 1 to 96th Rifle Corps, still in 6th Guards Army. Later that month it was moved with its Corps to 10th Guards Army, but on February 8 it returned to the Reserve of the Supreme High Command with its Corps for a substantial rebuilding. While there it was under command of 21st Army, and began moving to the south. When it returned to the fighting front on March 13 it was assigned to the 125th Rifle Corps of 47th Army in 2nd Belorussian Front.[50] When this formation of the Front was merged with 1st Belorussian Front in April the 185th was moved to 77th Rifle Corps, still in 47th Army, and it would remain under these commands for the duration of the war.[51]

Operation Bagration

At the start of the summer offensive against Army Group Center on June 22/23 the 77th Corps contained the 132nd, 143rd, 185th and 234th Rifle Divisions and 47th Army was one of five Armies on the western flank of the Front, south of the Pripyat Marshes in the area of Kovel, and so played no role in the initial stages of the offensive.[52] Colonel Aksyonov left the division on July 5 and remained in the training establishment for the duration. He was replaced on July 7 by Col. Aleksandr Vasilevich Glushko who had just completed studies at the Voroshilov Academy.

Lublin–Brest Offensive

The west wing Armies joined the offensive at 0530 hours on July 18, following a 30-minute artillery preparation. 47th Army's shock group had been shifted to its left flank during July 13-16. Forward detachments of battalion or regimental size attacked and soon determined that the German first and part of the second trench lines had been abandoned, so a further 110-minute preparation was cancelled. The leading Armies (47th, 8th Guards and 69th) reached the second defense zone along the Vyzhuvka River on July 19 and quickly forced a crossing, which led to the zone's collapse by noon, followed by a pursuit of the defeated forces, advancing 20-25km.[53]

On July 20 the leading Armies reached the final defense line along the Western Bug River and began taking crossing points off the march with their mobile units. 47th Army was now being led by the 2nd Guards Cavalry Corps, and by dusk was fighting along a line from outside Zalesie to Grabowo to Zabuzhye after a further advance of 18-26km. The Front's forces were now in a position to begin the encirclement of the German forces around Brest.[54]

The main forces of the Front's left wing were directed against Lublin on July 21, while 47th Army, along with a mobile group of 2nd Guards Cavalry and 11th Tank Corps, was tasked with reaching Siedlce. By the end of July 23 the Army had reached the line Danze–Podewucze–Pszwloka, following an advance of 52km in three days. By July 27 it was running into greater resistance, especially in the area of Biała Podlaska and Mendzizec, which blocked the encirclement of part of the Brest grouping. On July 29 Brest was finally encircled and taken, with Siedlce falling on July 31. By this time, 47th Army was spread across a front of 74km. Meanwhile, on July 28 the 2nd Tank Army was approaching the Praga suburb of Warsaw, which the STAVKA soon gave orders to be seized, along with bridgeheads over the Vistula River. This Army's attack soon ran into heavy resistance and stalled. The Praga area contained complex and modern fortifications and would prove a hard nut to crack. The German command soon struck with a powerful counterattack of five panzer and one infantry divisions against the boundary of 2nd Tank and 47th Armies in an effort to hold the place, and 2nd Tank was ordered not to attempt to storm the fortifications, but to wait for heavy artillery. In addition, both Armies were suffering severe shortages of fuel and ammunition after the long advance.[55]

Battle for Praga

The Front commander, Marshal K. K. Rokossovskii, planned to take Praga no later than August 8. This was to be carried out by the 2nd Tank, 47th, 28th and 70th Armies. By August 9 it was clear this had failed, and in fact some ground had been lost. The next day, the 47th was to launch an attack toward Kossow and Wyszków.[56] On the same day, Colonel Glushko was mortally wounded. He was replaced by Col. Nikolai Vasilevich Smirnov, who had previously led the 354th Rifle Division, who in turn was replaced by Col. Zenovii Samoilovich Shekhtman on August 22. This officer had begun the war as commander of the 1077th Rifle Regiment of the famous 316th Rifle Division, and had held three divisional commands before the 185th.

On September 5, most of the Front went over to the defensive,[57] but the battle for Praga went on until September 14, when the fortress was finally taken, and the division received its name as its second honorific:

PRAGA – ... 185th Rifle Division (Colonel Shekhtman, Zenovii Samoilovich)... The troops that participated in the battles for the liberation of the Praga fortress, by order of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief of 14 September 1944 and a commendation in Moscow, are given a salute of 20 artillery salvoes by 224 guns.[58]

Despite this success, Colonel Shektman was removed from his command on November 18, and did not see frontline service again. He was replaced by Col. Ivan Vasilevich Gruzdov, who had been serving as Shektman's deputy commander. On November 25, he was in turn replaced by Col. Mikhail Maksimovich Muzykin, who would remain in command for the duration. This officer had previously led the 304th Rifle Division, and on April 6, 1945, would be made a Hero of the Soviet Union.[59]

Vistula–Oder Offensive

In November, command of 1st Belorussian Front was transferred to Marshal Zhukov. The Front was ordered to launch a supporting attack north of Warsaw with the 47th along a 4km-wide front for the purpose of clearing the German forces between the Vistula and Western Bug, in conjunction with the left wing of 2nd Belorussian Front. Following this the Army was to outflank Warsaw from the northeast and help capture the city in cooperation with the 1st Polish Army and part of 61st and 2nd Guards Tank Armies.[60]

The main offensive began on January 12, 1945, but 47th Army did not begin its attack until January 15, with a 55-minute artillery preparation. By day's end it had cleared the inter-river area east of Modlin. Overnight the Army's 129th Rifle Corps forced a crossing of the frozen Vistula. On January 17 the 1st Polish Army began the fight for Warsaw and, threatened with encirclement, the German garrison abandoned it.[61] For their parts in the victory two regiments of the 185th received a battle honor:

WARSAW – ... 257th Rifle Regiment (Lt. Colonel Orlov, Anatolii Fyodorovich)... 695th Artillery Regiment (Lt. Colonel Ganzhara, Moisei Stepanovich)... The troops that participated in the battles for the liberation of Warsaw, by order of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief of 17 January 1945, and a commendation in Moscow, are given a salute of 24 artillery salvoes by 324 guns.[62]

The next day another regiment gained a similar honor:

SOCHACZEW – ... 280th Rifle Regiment (Lt. Colonel Ivanov, Pavel Leontevich)... The troops that participated in the battles for the towns of Sochaczew, Skierniewice, and Łowicz, by order of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief of 18 January 1945, and a commendation in Moscow, are given a salute of 20 artillery salvoes by 224 guns.[63]

Following these successes the STAVKA ordered an all-out advance to the Oder River. 47th Army reached the Bzura by 1800 hours that same day. As the Front's right flank lengthened to 110-120km by January 25 the 47th, 1st Polish, and 3rd Shock Armies were brought up to guard against any counteroffensive from German forces in East Pomerania. By the end of the next day elements of the Army captured Bydgoszcz and Nakło nad Notecią.[64]

Over the following weeks the Front's right wing forces eliminated the German garrisons blockaded in Schneidemühl, Deutsch Krone, and Arnswalde, but otherwise gained only up to 10km of ground.[65] For their roles in the taking of Schneidemühl the 257th Rifle Regiment would receive the Order of Suvorov, 3rd Degree, while the 1319th Rifle Regiment was given the Order of Kutuzov, 3rd Degree, both on April 5.[66] The German 11th Army launched a hastily-planned counteroffensive at Stargard on February 15 and two days later the 47th Army was forced to abandon the towns of Piritz and Bahn and fall back 8-12km.[67]

East Pomeranian Offensive

After the Stargard offensive was shut down on February 18, Zhukov decided split the 11th Army by attacking toward the Baltic Sea. 47th Army was tasked with reaching and taking the city of Altdamm.[68] This was accomplished on March 20, and as a result, on April 26 the 185th would be awarded the Order of Suvorov, 2nd Degree, for its part in retaking Stargard and capturing several other towns in Pomerania, including Bärwalde, Tempelburg, and Falkenburg; on May 3 the following awards would be made to subunits of the division for the fighting for Altdamm:

- 695th Artillery Regiment - Order of Alexander Nevsky

- 49th Antitank Battalion - Order of Alexander Nevsky

- 340th Sapper Battalion - Order of Alexander Nevsky

- 194th Signal Battalion - Order of the Red Star[69]

Berlin Offensive

At the start of the final offensive on the German capital the 47th Army was deployed in the bridgehead over the Oder at Küstrin on a 8km-wide sector. It was planned to make its main strike in the center, a 4.3km sector from Neulewin to Neubarnim. 77th Corps consisted of the 185th, 260th and 328th Rifle Divisions and was on the Army's right flank. The 260th was in first echelon, with the other two divisions in second. At this time the rifle division's strengths varied between 5,000 and 6,000 men each. The divisions in first echelon had the immediate goal of penetrating the defense to a depth of 4.5-5km, which would carry them through the first two German positions. The Army was supported by 101 tanks and self-propelled guns.[70]

The offensive began before dawn on April 16 on the sectors of 1st Belorussian and 1st Ukrainian Fronts. A massive artillery bombardment was launched at 0500 hours, except on the fronts of 47th and 33rd Armies. On 47th Army's front the bombardment started 0550 and lasted 25 minutes. The infantry went into the attack at 0615 against defenders that were badly shaken and had suffered significant casualties. The 260th Division made good progress and later in the day either the 185th or the 328th was committed from second echelon. By day's end the leading troops had advanced 4-6km.[71]

Zhukov ordered that the attack continue through the night, following a 30-40-minute artillery preparation, so as to break through the intermediate defense position. 47th Army made some progress through the dark, but its general offensive began at 0800 hours after another 30-minute preparation. 77th Corps, still with two divisions up and one behind, captured a strongpoint at Eichwerder, and by dusk had reached the eastern fringes of another strongpoint at Wriezen in the second defense zone, following an advance of 5km and having repelled several counterattacks. Overnight, the troops of the Front consolidated their positions and took part in reconnaissance. After a short artillery preparation the offensive continued on the morning of April 18.[72]

47th Army stepped off at 1000 hours after a 40-minute bombardment. During the day, 77th Corps was fully involved in the fighting for Wriezen against the 606th Volksgrenadier Division, reinforced by the 109th Reserve Regiment. By the end of the day the southern outskirts had been captured, which effectively broke through second defensive zone and eventually reached the woods 1,000m to the southwest, for a total advance of 1-3km. During this battle the Corps' remaining second echelon division was committed. Despite this success, and others, Zhukov was becoming concerned that the offensive was proceeding too slowly, and ordered that steps be taken to improve command and control, beginning on April 19. In addition, the 47th, as well as the 3rd Shock and 5th Shock Armies shift their axes of attack from northwest and west to west and southwest, with the objective of breaking into Berlin as quickly as possible. Specifically, the 47th was directed to advance on Haselberg, Baiersdorf, Schildow, and Hermsdorf; these last two were in the northern part of the city.[73]

Fighting on April 19 was focused on the third defensive zone which now contained German reserves moved up from the city. During the morning, 77th Corps completed the fight for Wriezen after a 30-minute bombardment using 262 guns, including 40 of 122mm-152mm calibre, most firing over open sights. 47th Army went over to the general attack at noon following another 30 minutes of artillery fire. The Corps again had two divisions up and one back, and by 2200 hours had reached the line from height 91.6 to the northwest outskirts of Haselberg before running into heavy fire that prevented any further advance. To the rear the 7th Guards Cavalry Corps was waiting for the infantry to produce a gap in the German lines at or near the boundary of 77th and 125th Corps.[74]

Encircling Berlin

47th, 3rd Shock and 5th Shock Armies were ordered on April 20 to continue a rapid advance during the day with their first echelons and through the night with their second echelons. The 47th now had the support of 9th Guards Tank Corps and 1st Mechanized Corps of 2nd Guards Tank Army. With this assistance the Army advanced 12km during the day, and the mobile troops as much as 22km, breaking through Berlin's outer ring on a 8km sector from Leuenberg to Tiefensee. Overnight the Army cleared Bernau in cooperation with 9th Guards Tanks. Zhukov's first priority for the next day was to preempt and German effort to organize on the inner ring. The Army responded by taking Schenow, Zepernick and Buch.[75]

On April 22, 47th Army, still with 9th Guards Tanks, continued attacking to the west in an effort to envelop the city from the north. By 2000 hours the leading infantry began crossing the Havel River. Only 60km remained between the Army and 1st Ukrainian Front's 4th Guards Tank Army advancing from the south. 77th Corps was now moved back to the Army's second echelon. For the next day the 47th was directed to reach the area of Spandau, then detach one division with one tank brigade from 9th Guards Tanks to drive towards Potsdam and take it, cutting the German retreat path from the city to the west. 77th Corps, still in second echelon, crossed the Havel and concentrated near Betzow and Schoenwalde. During the day the Army had covered another 8km to the west, crossed two corps over the Havel, and turned its front to the southwest. Overnight, Zhukov ordered the Army to complete the encirclement, in conjunction 4th Guards Tanks, by taking a line from Paren to Potsdam. 77th Corps, still in its previous formation, was now attacking in cooperation with 9th Guards Tanks, which had moved through the dark to seize Nauen from the march at 0800. 77th Corps entered the town by 1300, and by day's end had recorded an advance of 16km. By now a gap of just 10km separated the two pincers. The objective for April 25 remained Potsdam. The 185th was now fighting defensively against German breakout efforts along the line Nauen to Etzin, while its main forces continued advancing to the south. At noon, men of the 328th Division, with tanks of the 6th Guards Tank Brigade, joined hands with 4th Guards Tank Army's 6th Guards Mechanized Corps, completing the encirclement of Berlin. By the end of the day 77th Corps was fighting in the northwest outskirts of Potsdam.[76]

The 185th continued its defense on April 26, while the 260th and 328th attacked into the city and into Potsdam respectively without making much progress. One important development was the 125th Corps linking up with units of 1st Ukrainian Front on the Havel near Gatow to cut off the German Potsdam grouping from the forces in Berlin. The following day the 185th and 328th, along with units of 9th Guards Tanks, 6th Guards Mechanized, and 10th Guards Tank Corps, liquidated the Potsdam grouping, taking 2,000 prisoners in the process. This victory effectively eliminated any chance of the Berlin grouping breaking out to the west. During April 28, 47th Army was mainly occupied with mopping up the Potsdam area before regrouping during the afternoon for an advance on Butzow with its main forces while two divisions, including the 185th, with units of the 6th Guards Mechanized and 7th Guards Cavalry would advance on Brandenburg an der Havel the next morning. This objective was secured on May 1.[77]

Postwar

The division ended the war as the 185th Rifle, Pankratovo-Praga, Order of Suvorov Division. (Russian: 185-я стрелковая Панкратовско-Пражская ордена Суворова дивизия.) In a final pair of awards on May 28 the 1319th Rifle Regiment received the Order of the Red Banner, while the 695th Artillery Regiment was given the Order of Bogdan Khmelnitsky, 2nd Degree, both for their parts in the capture of Brandenburg.[78] The next day the Group of Soviet Forces in Germany was formed, under the terms of STAVKA Order No. 11095, effective June 10.[79] By this time the division was under command of Col. Ivan Grigorievich Pavlovskii, who was promoted to the rank of major general on July 11. Colonel Muzykin was promoted on the same date and took over the 101st Guards Rifle Division in October. He continued to serve in a variety of commands and other roles and would be promoted to lieutenant general on February 18, 1958. He retired in January 1963 and died at Moscow on June 22, 1992.[80]

As of December 1 the 185th had been transferred to the 125th Rifle Corps. In February 1946 the 47th Army was disbanded, and its remaining units were withdrawn to the USSR. By April the division was at Kostroma and 125th Corps was disbanded. It was then sent to Kungur in the Ural Military District, where its remaining personnel were used to form the 27th Rifle Brigade in 1947.[81]

References

Citations

- ^ Charles C. Sharp, "The Deadly Beginning", Soviet Tank, Mechanized, Motorized Divisions and Tank Brigades of 1940 - 1942, Soviet Order of Battle World War II, Vol. I, Nafziger, 1995, p. 60

- ^ David M. Glantz, Stumbling Colossus, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 1998, p. 230

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1941, p. 11

- ^ Sharp, "The Deadly Beginning", p. 60

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1941, pp. 15, 23

- ^ Robert Forczyk, Demyansk 1942-43: The frozen fortress, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2012, Kindle ed.

- ^ Sharp, "The Deadly Beginning", p. 60

- ^ Sharp, "Red Tide", Soviet Rifle Divisions Formed From June to December 1941, Soviet Order of Battle World War II, Vol. IX, Nafziger, 1996, p. 25

- ^ Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941 - 1944, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 2002, pp. 63, 66, 91, 561

- ^ Sharp and Jack Radey, The Defense of Moscow 1941 - The Northern Flank, Pen & Sword Books Ltd., Barnsley, UK, 2012, pp. 23-24

- ^ Sharp and Radey, The Defense of Moscow 1941 - The Northern Flank, pp. 25-26, 258-59

- ^ Sharp and Radey, The Defense of Moscow 1941 - The Northern Flank, pp. 29-31, 55-57

- ^ Sharp and Radey, The Defense of Moscow 1941 - The Northern Flank, pp. 89-91. Soviet accounts state that Mednoye was taken on October 16.

- ^ Sharp and Radey, The Defense of Moscow 1941 - The Northern Flank, pp. 91-92, 105, 114

- ^ Sharp and Radey, The Defense of Moscow 1941 - The Northern Flank, pp. 115-16

- ^ Sharp and Radey, The Defense of Moscow 1941 - The Northern Flank, pp. 124-25

- ^ Sharp and Radey, The Defense of Moscow 1941 - The Northern Flank, pp. 126-29, 132, 134

- ^ Sharp and Radey, The Defense of Moscow 1941 - The Northern Flank, pp. 135-36, 162-63

- ^ Sharp and Radey, The Defense of Moscow 1941 - The Northern Flank, pp. 137-38, 146-48, 160-61

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1941, pp. 62, 74

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Moscow, ed. & trans, R. W. Harrison, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2015, Kindle ed., Part III, ch. 3

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Moscow, Kindle ed., Part III, ch. 3

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Moscow, Kindle ed., Part IV, chs. 1, 2

- ^ https://www.warheroes.ru/hero/hero.asp?Hero_id=1293. In Russian; English translation available. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Moscow, Kindle ed., Part IV, ch. 2

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Moscow, Kindle ed., Part IV, ch. 1

- ^ Svetlana Gerasimova, The Rzhev Slaughterhouse, ed. & trans. S. Britton, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2013, pp. 26, 28, 30

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1942, p. 26

- ^ Gerasimova, The Rzhev Slaughterhouse, pp. 37, 39-41

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1942, p. 63

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1942, p. 101

- ^ Gerasimova, The Rzhev Slaughterhouse, pp. 56-57, 59-60, 62-64, 66, 69

- ^ Glantz, Zhukov's Greatest Defeat, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 1999, pp. 61-63

- ^ Glantz, Zhukov's Greatest Defeat, pp. 140-43

- ^ Glantz, Zhukov's Greatest Defeat, pp. 144-45

- ^ Glantz, Zhukov's Greatest Defeat, p. 146

- ^ Glantz, Zhukov's Greatest Defeat, pp. 147-50

- ^ Glantz, Zhukov's Greatest Defeat, pp. 208-10

- ^ Glantz, Zhukov's Greatest Defeat, pp. 211-14

- ^ Glantz, Zhukov's Greatest Defeat, pp. 215-18, 274-79

- ^ Gerasimova, The Rzhev Slaughterhouse, p. 221

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, pp. 83, 187

- ^ http://www.soldat.ru/spravka/freedom/1-ssr-5.html. In Russian. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, p. 245

- ^ Glantz, Battle For Belorussia, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 2016, pp. 37-38, 40

- ^ Glantz, Battle For Belorussia, pp. 39-42

- ^ Earl F. Ziemke, Stalingrad to Berlin, Center of Military History United States Army, Washington, DC, 1968, p. 203

- ^ Glantz, Battle for Belorussia, pp. 146-51, 154

- ^ Glantz, Battle for Belorussia, pp. 235-40

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, pp. 10, 38, 87, 103

- ^ Sharp, "Red Tide", p. 25

- ^ Walter S. Dunn, Jr, Soviet Blitzkrieg, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2008, pp. 209-11

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Operation Bagration, ed. & trans. R. W. Harrison, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2016, Kindle ed., vol. 2, part 2, ch. 11

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Operation Bagration, Kindle ed., vol. 2, part 2, ch. 11

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Operation Bagration, Kindle ed., vol. 2, part 2, ch. 11

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Operation Bagration, Kindle ed., vol. 2, part 2, ch. 12

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Operation Bagration, Kindle ed., vol. 2, part 2, ch. 12

- ^ http://www.soldat.ru/spravka/freedom/9-poland.html. In Russian. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ https://www.warheroes.ru/hero/hero.asp?Hero_id=13846. In Russian; English translation available. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Prelude to Berlin, ed. & trans. R. W. Harrison, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2016, pp. 48-49, 51, 74, 546

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Prelude to Berlin, p. 74

- ^ http://www.soldat.ru/spravka/freedom/9-poland.html. In Russian. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ http://www.soldat.ru/spravka/freedom/9-poland.html. In Russian. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Prelude to Berlin, pp. 75-77, 208, 217

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Prelude to Berlin, p. 305

- ^ Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967b, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Prelude to Berlin, pp. 305-06

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Prelude to Berlin, p. 310

- ^ Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967b, pp. 122, 175–78.

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Berlin Operation 1945, ed. & trans. R. W. Harrison, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2016, Kindle ed., ch. 11

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Berlin Operation 1945, Kindle ed., ch. 12

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Berlin Operation 1945, Kindle ed., ch. 12

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Berlin Operation 1945, Kindle ed., ch. 12

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Berlin Operation 1945, Kindle ed., ch. 12

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Berlin Operation 1945, Kindle ed., ch. 15

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Berlin Operation 1945, Kindle ed., ch. 15

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Berlin Operation 1945, Kindle ed., ch. 19. At one point this source misidentifies the 185th as the 175th Rifle Division.

- ^ Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967b, pp. 280–81.

- ^ STAVKA Order No. 11095

- ^ https://warheroes.ru/hero/hero.asp?Hero_id=13846

- ^ Feskov et al 2013, pp. 383, 498, 512.

Bibliography

- Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union (1967b). Сборник приказов РВСР, РВС СССР, НКО и Указов Президиума Верховного Совета СССР о награждении орденами СССР частей, соединениий и учреждений ВС СССР. Часть II. 1945 – 1966 гг [Collection of orders of the RVSR, RVS USSR and NKO on awarding orders to units, formations and establishments of the Armed Forces of the USSR. Part II. 1945–1966] (in Russian). Moscow.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Feskov, V.I.; Golikov, V.I.; Kalashnikov, K.A.; Slugin, S.A. (2013). Вооруженные силы СССР после Второй Мировой войны: от Красной Армии к Советской [The Armed Forces of the USSR after World War II: From the Red Army to the Soviet: Part 1 Land Forces] (in Russian). Tomsk: Scientific and Technical Literature Publishing. ISBN 9785895035306.

- Grylev, A. N. (1970). Перечень № 5. Стрелковых, горнострелковых, мотострелковых и моторизованных дивизии, входивших в состав Действующей армии в годы Великой Отечественной войны 1941-1945 гг [List (Perechen) No. 5: Rifle, Mountain Rifle, Motor Rifle and Motorized divisions, part of the active army during the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945] (in Russian). Moscow: Voenizdat. pp. 90, 204

- Main Personnel Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union (1964). Командование корпусного и дивизионного звена советских вооруженных сил периода Великой Отечественной войны 1941–1945 гг [Commanders of Corps and Divisions in the Great Patriotic War, 1941–1945] (in Russian). Moscow: Frunze Military Academy. pp. 194–95, 337