May 16 coup

| May 16 coup | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

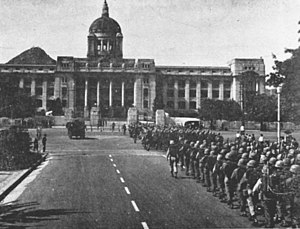

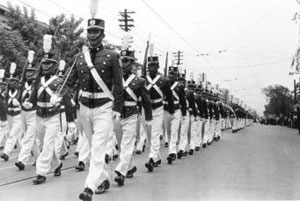

From top to bottom, Major-General Park Chung Hee (front center) and soldiers tasked with effecting the coup, South Korean Marines march to the capitol after the coup, and officer cadets of Korea Military Academy march in support of the military coup | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| May 16 Coup | |

| Hangul | 5·16 군사정변 |

|---|---|

| Hanja | 五一六軍事政變 |

| Revised Romanization | O-illyuk gunsa jeongbyeon |

| McCune–Reischauer | O-illyuk kunsa chŏngbyŏn |

The May 16 military coup d'état (Korean: 5·16 군사정변) was a military coup d'état in South Korea in 1961, organized and carried out by Park Chung Hee and his allies who formed the Military Revolutionary Committee, nominally led by Army Chief of Staff Chang Do-yong after the latter's acquiescence on the day of the coup. The coup rendered powerless the democratically elected government of Prime Minister Chang Myon and President Yun Posun, and ended the Second Republic, installing a reformist military Supreme Council for National Reconstruction effectively led by Park, who took over as chairman after Chang's arrest in July.

The coup was instrumental in bringing to power a new developmentalist elite and in laying the foundations for the rapid industrialization of South Korea under Park's leadership, but its legacy is controversial for the suppression of democracy and civil liberties it entailed, and the purges enacted in its wake. Termed the "May 16 Military Revolution" by Park and his allies, "a new, mature national debut of spirit",[1] the coup's nature as a "revolution" is controversial and its evaluation contested.

Background and causes

The background to the coup can be analysed both in terms of its immediate context and in terms of the development of post-liberation South Korea. Although the singularly problematic economic and political climate of the Second Republic encouraged a military intervention, the roots of the coup go back to the late Rhee period. Historians like Yong-Sup Han argue that the common view of the coup as caused solely by the vagaries of a new regime paralyzed by instability is too simplistic.[2]

South Korea under Syngman Rhee

From 1948, South Korea was governed by President Syngman Rhee, an anti-Communist who used the Korean War to consolidate a monopoly on political power in the republic. Rhee represented the interests of a conservative ruling class, the so-called "liberation aristocrats" who had risen to positions of influence under American occupation. These "liberation aristocrats" formed the bulk of the political class, encompassing both Rhee's supporters and his rivals in the Democratic Party, which advanced a vision of society broadly similar to his own.[3] Rhee eliminated any significant source of real opposition, securing for example the execution of Cho Bong-am, who had campaigned against him in the presidential elections of 1956 on a platform of peaceful reunification and had attracted some 30% of the vote, an unacceptably high level of support for an opposition candidate.[4]

Even such significant opposition figures as Cho, however, can be considered to have been part of the broad conservative consensus of the governing class,[5] which rested on a traditionalist, Confucian worldview that saw "pluralism in ideology and equality in human relationships [as] foreign concepts",[6] and which upheld the value of paternalist government and the power of extensive networks of political patronage. Rhee, under this traditionalist model, was the foremost "elder" in Korean society, to whom Koreans owed familial allegiance, and this relationship was strengthened by the ties of obligation that connected Rhee to many in the ruling class.[6]

One result of the rule of the "liberation aristocrats" was the stalling of development in South Korea, in marked contrast to the situation in nearby Japan. Where South Korea had been intensively developed under the Japanese colonial system, Rhee's presidency saw little significant effort to develop the South Korean economy, which remained stagnant, poor and largely agrarian.[7] The lack of development under Rhee provoked a growing nationalistic intellectual reaction which called for a radical restructuring of society and a thorough political and economic reorganization. Park Chung Hee, the later leader of the May Coup who at that time was a second-tier army officer with decidedly ambiguous political leanings,[8][9] was heavily influenced by this unfolding intellectual reaction.[10]

Social and economic problems of the Second Republic

After rigged elections in March 1960, growing protests developed into the April Revolution, and Rhee was pressured by the United States into a peaceful resignation on April 26. With Rhee out of the way, a new constitution was promulgated establishing the Second Republic, and legislative elections on June 29 resulted in a landslide victory for the Democratic Party, with Rhee's Liberals reduced to a mere two seats in the newly constituted lower house of the National Assembly.[11] The Second Republic adopted a parliamentary system, with a figurehead president as head of state; executive power was effectively vested in the prime minister and cabinet. Democrat Yun Posun was elected as president in August, with former vice-president Chang Myon becoming prime minister.[12]

The Second Republic was beset with problems from the start, with bitter factionalism in the ruling Democratic Party competing with implacable popular unrest for the government's attention. The South Korean economy deteriorated under heavy inflation and high rates of unemployment, while recorded crime rates more than doubled; from December 1960 to April 1961, for example, the price of rice increased by 60 percent, while unemployment remained above 23%.[12] Widespread food shortages resulted. Chang, meanwhile, representing the Democratic Party's "New Faction", had been elected prime minister by the thin margin of three votes.[12] Purges of Rhee's appointees were rendered ineffective in the public eye by Chang's manipulation of the suspect list to favour wealthy businessmen and powerful generals.[13] Although Rhee had been removed and a democratic constitution instituted, the "liberation aristocrats" remained in power, and the worsening problems facing South Korea were proving insurmountable for the new government.[citation needed]

The breakdown of South Korean politics and the administrative purges racking the army combined to demoralise and discourage the Military Security Command, which was charged with the maintenance of the chain of command in the military and weeding out insubordination.[14] The reluctance of the Military Security Command to act allowed plans for a coup to unfold, and the problems of the Second Republic provided the context for the coup to be organised and realised.[15]

Factionalism in the military

A direct factor in paving the way to the coup was factionalism in the South Korean army itself, one of the largest in the world at the time with 600,000 soldiers.[16] The army had been given a distinctive identity by the dual Japanese and subsequently American training that many of its members had received, "combin[ing] the Japanese militarist ethos with the American spirit of technical efficiency to expand its mission from defending the country against communist aggression to that of helping it build itself into a modern nation".[16] Reformist junior officers viewed the senior generals as having been corrupted by party politics, and the problem was compounded by a bottleneck in promotions caused by the consolidation of the positions of the senior commanders of the army after the end of its rapid expansion in the Korean War.[17]

The army was also divided along regional lines and between factions of officers who had graduated from the same school. Of the latter, the most influential were the competing factions who had graduated from the Japanese Military Academy and from the Manchurian officers' school at Xinjing respectively, while more lower-ranked officers were divided by their class of graduation from the post-liberation Korean Military Academy.[18] Park had attended all three institutions, and was uniquely positioned to lead what would become the coup coalition, with his extensive ties among both the senior commanders of the army and the younger factions.[18]

After the overthrow of the Rhee regime and the institution of the Second Republic, the reformists, led by KMA alumni, began to call for the senior commanders to be held to account for complicity in the rigging of the 1960 and 1956 presidential elections.[19] Park, relatively high-ranking as Major General, threw himself into the spotlight by declaring his support for the reformists and demanding the resignation of Army Chief of Staff Song Yo-chan on May 2.[8][20] On September 24, 16 colonels, led by Kim Jong-pil, demanded the resignation of Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Choi Yong-hui in an incident known as the "revolt against seniors" (하극상 사건; 下剋上事件; hageuksang sageon). By this point, initial plans for a coup were already advanced, and they were accelerated by the "revolt against seniors".[21]

Planning and organization

Central organization

The first plan for a military coup to evolve was the so-called "May 8 plan", a plan calling for a putsch on May 8, 1960. This plan was discussed and formulated at the start of 1960 by reformist officers including Park, and was aimed at unseating Rhee from the presidency.[22] This plan never moved significantly beyond being an idea, and was soon superseded by the April Revolution. From May to October 1960, however, Park assembled a variety of officers to organize a new plan for a coup, largely on the basis of his ties with other graduates of the Manchurian Military Academy. He also secured the loyalty of the editor of the Pusan Daily News, aiming to ensure a propaganda basis for the coup. By October, Park had gathered nine core members, tasking his close associate Kim Jong-pil with the role of general secretary.[23]

Fortuitously in November, Park was transferred from his post at Pusan to Seoul, and at a meeting on November 9 at his Seoul residence, the core group decided that they would manipulate the anti-corruption movement within the military to support their aims. Furthermore, it was decided that Park would focus on building support for the coup among other generals, while the other core members would recruit younger officers and construct revolutionary cells within and outside Seoul.[14] By Chang Do-yong's account, however, on January 12, 1961, it was discovered that Park had been placed on a list of 153 officers scheduled to be moved to the Reserve Army in May.[24] This discovery would likely have accelerated the plans for the coup.[25] The historian Kim Hyung-A suggests by contrast that it is possible that Chang, as Army Chief of Staff, deliberately spread the rumors of Park's imminent removal in order to provide political cover for the coup; he concludes that "it is obvious that Park had received extraordinary support from someone in power".[24]

Immediate preparation

Over the course of the next half-year, the coup plans became an open secret within the military. Park failed in winning over the army's Counter-Intelligence Command and the 9th Division, but neither organization reported the plans to higher authorities, allowing the planning to proceed unimpeded. As 1960 drew to a close, moreover, Park began parallel talks outside of his core group, structuring a loose network of supporters for his plan; among those brought in by these talks was Major General Lee Chu-il, with whom Park agreed that once the coup had taken place, Chang Do-yong would be placed as head of the Revolutionary Council in order to get the entire army's support.[26] In March 1961, the core group met at the Chungmu-jang Restaurant in Seoul, and fixed the date April 19 for the coup, expecting significant disturbances on that day due to its being the anniversary of the revolution that had overthrown Rhee's regime. Park also secured the financial backing of prominent businessmen, amassing a total of 7.5 million hwan.[27]

Finally, on April 10, 1961, Park took the initiative in revealing the details of the plan to Chang Do-yong himself.[28] Chang's subsequent ambivalent response was decisive in allowing the coup to take place. While he turned down the leadership position offered to him, he neither informed the civilian government of the plan, nor ordered the arrest of the conspirators.[28] This allowed Park to present Chang as an "invisible hand" guiding the organization of the coup. According to Han, this ambivalence was most likely because Chang had calculated that the coup organizers had by this time gathered too much momentum to stop, though this analysis assumes Chang's earlier non-involvement.[28] The date of April 19 passed without the expected disturbances, however, and the planners rescheduled the coup for May 12.[27]

Failed coup of May 12 and emergency planning

Some time shortly after this, the May 12 plan was finally leaked by accident to the military security forces, who reported it to Prime Minister Chang Myon and Defense Minister Hyeon Seok-ho. Chang Myon was dissuaded from commissioning an investigation by the intervention of Army Chief of Staff Chang Do-yong, who convinced him that the security report was unreliable. Pervasive unrealized rumours of the imminence of a military coup also contributed to Chang Myon's decision, and the report on the May 12 plan was dismissed as a false alarm. The coup organizers responded by aborting the May 12 plan and fixing a new, and final, date and time, 3am on May 16.[29]

Course of events

The plot was leaked once again early in the morning of May 16, and this time immediate action was taken.[30] The Counter-Intelligence Command raised an alert that a mutiny was underway, and a detachment of military police was sent to round up the suspected perpetrators. Park moved to the Sixth District Army Headquarters,[14] now Mullae Park,[31] to take personal control of the coup operations and salvage the plan. Park gave a speech to the assembled soldiers, saying:

We have been waiting for the civilian government to bring back order to the country. The Prime Minister and Ministers, however, are mired in corruption, leading the country to the verge of collapse. We shall rise up against the government to save the country. We can accomplish our goals without bloodshed. Let us join in this Revolutionary Army to save the country.

The speech was so successful that even the military police who had been dispatched to arrest the mutineers defected to their cause.[30] With the Sixth District Army now secure under his control, Park chose Colonel Kim Jae-chun to organize the vanguard of the occupation of Seoul and dispatched a message to Chang Do-yong, instructing him to definitively join the coup or suffer the consequences of association with the civilian government. He then departed for Special Warfare Command, where he issued instructions to cross the Han River and occupy the presidential residence at the Blue House.

Meanwhile, an artillery brigade occupied the central Army Headquarters and secured the downtown areas of Seoul north of the Han. By 4:15am, after a brief exchange of fire with loyalist military police who were guarding the bridge across the Han, Park's forces had occupied the administrative buildings of all three branches of government.[32] They proceeded to seize the headquarters of the Korean Broadcasting System, issuing a proclamation announcing the Military Revolutionary Committee's seizure of power:

The military authorities, thus far avoiding conflict, can no longer restrain themselves, and have taken a concerted operation at the dawn of this day to completely take over the three branches of the Government ... and to form the Military Revolutionary Committee. ... The armed services have staged this uprising because:

(1) We believe that the fate of the nation and the people cannot be entrusted to the corrupt and incompetent regime and its politicians.

(2) We believe that the time has come [for the armed forces] to give direction to our nation, which has gone dangerously astray.

— Military Revolutionary Committee[32]

The broadcast went on to outline the policy objectives of the coup, including anti-communism, strengthening of ties with the United States, the elimination of political corruption, the construction of an autonomous national economy, Korean reunification, and the removal of the present generation of politicians.[32] The proclamation was issued in the name of Chang Do-yong, who was referred to as the chairman of the committee, but this was without his prior approval.[34] When dawn broke, a marine corps unit under Kim Yun-geun crossed the Han River and took control of the Blue House as instructed.

The civilian government rapidly imploded. Prime Minister Chang Myon had fled Seoul on hearing of the coup, and President Yun Posun accepted the coup as a fait accompli.[30] Yun continued to serve as nominal head of state until 1963, though stripped of all effective power. Commander Lee Han-lim of the First Army had prepared to mobilize the reserves to suppress the coup, but backed down to prevent an opportunity for a North Korean attack. He was arrested two days later.[35] Twenty heavily armed divisions now stood in support of the coup in Seoul, preventing any realistic chance of its suppression. After three days of hiding, Chang Myon reappeared to announce the resignation of the entire cabinet, and ceded power to the new junta.[36] Army cadets marched through the streets proclaiming their support for the coup. Chang Do-yong now accepted his appointment as chairman of the committee, granting it the final stamp of authority that it required. The May 16 coup was now complete.[36]

Aftermath

Consolidation and power struggle

The business of consolidating a new government began soon after the coup had been completed. Martial law was immediately put into force. On May 20, the Military Revolutionary Committee was renamed the Supreme Council for National Reconstruction (SCNR), and the following day a new cabinet was instituted.[37] Chang Do-yong, the chairman of the committee, remained Army Chief of Staff, but also took on the additional offices of Prime Minister and Defense Minister, becoming formal head of the administration.[38] The SCNR was formalized as a junta of the 30 highest-ranking military officers initially arranged in 14 subcommittees, and assumed a wide-ranging responsibility that included the powers to promulgate laws, appoint cabinet posts, and oversee the functioning of the administration as a whole.[37]

The constitution of the new cabinet was the subject of an intense internal power struggle, however, and over the course of the next two months Park soon engineered a rapid transfer of power into his own hands. On June 6, the SCNR promulgated the Law Regarding Extraordinary Measures for National Reconstruction, which stripped Chang of his posts of Defense Minister and Army Chief of Staff. Much of this law was drafted by Yi Seok-che, who was operating under instructions from Park to "eliminate" Chang.[38] Four days later, on June 10, the Supreme Council for National Reconstruction Law was enacted, which specified that the deputy chairman of the SCNR would be chairman of its standing committee, granting Park additional powers. Finally, on July 3, Chang himself was arrested on a charge of conspiracy to carry out a counter-coup, and the June 10 law was amended to allow Park to assume the office of chairman both of the SCNR and its Standing Committee.[38]

United States response

Part of the immediate task of the coup leaders was to secure American approval for their new government. This approval came quickly, as on May 20, President John F. Kennedy dispatched a message to the SCNR confirming the friendship between the two countries. Carter B. Magruder, commander-in-chief of the United Nations Command, simultaneously announced the return to the ROK Army of all rights of operational command.[39] By May 27, the coup leaders were confident in American support and dissolved the martial law they had imposed on the day of the coup.[36] On June 24, American Ambassador Samuel D. Berger arrived in Seoul, and reportedly informed Park that the United States was interested in publicly supporting his government, but required the cessation of "purges and recriminations".[40] Finally, on July 27, Secretary of State Dean Rusk announced the United States' official recognition of the SCNR government at a press conference.[41]

State building

A significant development occurred soon after the coup with the planning and subsequent establishment of the Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA). Members of the Military Revolutionary Committee were briefed on May 20 by Kim Jong-pil on the intended functions of this new agency. The KCIA was realized on June 10 with the enactment of Law No. 619, which brought the agency into being under the direction of Kim Jong-pil. The KCIA would be Park's central power base throughout his leadership of South Korea, and it served an important function from the outset, granting Kim and Park the ability to remove Chang from the council and to initiate a series of wide-ranging purges of civilian institutions.[42]

The KCIA was supported in this latter work by the Inspection Committee on Irregularities in the Public Service.[42] The purges of state ministries were escalated by the announcement on July 20 of a policy programme aiming at the forced retirement of almost 41,000 "excess" bureaucrats and the reduction of the number of civil servants by 200,000.[43] The purges of the government apparatus, Park's triumph in the power struggles that followed the May coup, and his eventual election as civilian president in 1963 set the stage for the consolidation of his developmental regime.[44]

Legacy and evaluation

The May 16 coup was the starting point of a series of military regimes that would last in some form until 1993. It also provided a precedent for the December Twelfth and the May Seventeenth coups of Chun Doo-hwan, Park's effective successor. With the development of a concerted opposition under Park and its evolution into the Gwangju Democratization Movement after 1980, the coup became the subject of much controversy, with many opponents of the military regime, such as Kim Dae Jung, looking back on the coup as an unjustified act of insurrectionary violence that toppled South Korea's first genuinely democratic government.[45] Others point to the positive legacy of the coup, however, such as the 1994 Freedom House analysis which refers to the rapid industrialization that followed the coup and the "uncorrupt" nature of Park's rule.[46]

Name

In official discourse before 1993, the coup was referred to as the "May 16 Revolution" (5·16 혁명; 五一六革命; O-illyuk hyeongmyeong), but under the reforming non-military administration of erstwhile opposition leader Kim Young-sam, the event was re-designated as a coup or military insurrection (군사 정변; 軍事政變; gunsa jeongbyeon). Park had described the "May Revolution" as an "unavoidable ... act of self-defense by and for the Korean people",[47] and in the historiography of the military regimes, the Revolution was presented as having been the result of the will of the nation as a whole. Kim Young-sam's re-designation of the event rejected this analysis, and was accompanied by the corresponding recognition of the April 1960 demonstrations as the "April Revolution". This reading was cemented in 1994–95 with curriculum reforms and the issuing of history textbooks applying the new labels.[48]

See also

References

- ^ Jager 2003, p. 79.

- ^ Kim & Vogel 2011, p. 35.

- ^ Kim 2004, p. 42.

- ^ Koo 1993, p. 42.

- ^ Kim & Cho 1972, p. 45.

- ^ a b Kim 2004, p. 43.

- ^ Kohli 2004, p. 62.

- ^ a b Kim & Vogel 2011, p. 44.

- ^ Lee 2006, p. 46.

- ^ Kim 2004, p. 40.

- ^ Nohlen & Grotz 2001, p. 420.

- ^ a b c Kim 2004, p. 45.

- ^ Kim 2004, p. 46.

- ^ a b c d Kim & Vogel 2011, p. 46.

- ^ Kim & Vogel 2011, pp. 45–46.

- ^ a b Kim & Vogel 2011, p. 41.

- ^ Kim & Vogel 2011, p. 42.

- ^ a b Kim & Vogel 2011, p. 39.

- ^ Kim & Vogel 2011, p. 43.

- ^ Kim 2004, p. 68.

- ^ Kim 2004, p. 62.

- ^ Kim 2003, p. 134.

- ^ Kim & Vogel 2011, p. 45.

- ^ a b Kim 2004, p. 63.

- ^ Kim 2004, p. 64.

- ^ Kim & Vogel 2011, p. 47.

- ^ a b Kim & Vogel 2011, p. 49.

- ^ a b c Kim & Vogel 2011, p. 48.

- ^ Kim & Vogel 2011, pp. 49–50.

- ^ a b c Kim & Vogel 2011, p. 50.

- ^ "철공소 골목의 변신! 문래근린공원·문래창작촌". mediahub.seoul.go.kr (in Korean). Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ a b c Kim & Vogel 2011, p. 51.

- ^ "Heroic general Lee passes away at age of 91". The Korea Times. April 30, 2012. Retrieved April 30, 2012.

- ^ Kim & Vogel 2011, p. 52.

- ^ Kim & Vogel 2011, p. 53.

- ^ a b c Kim & Vogel 2011, p. 54.

- ^ a b Kim & Vogel 2011, p. 88.

- ^ a b c Kim & Vogel 2011, p. 89.

- ^ Kim 2004, p. 70.

- ^ Kim 2004, p. 71.

- ^ Kim 2004, p. 72.

- ^ a b Kim & Vogel 2011, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Kim & Vogel 2011, p. 92.

- ^ Kim & Vogel 2011, p. 99.

- ^ Kim 1997, p. 73.

- ^ Freedom House 1994, p. 348.

- ^ Kim 2007, p. 94.

- ^ Seth 2002, p. 233.

Sources

- Freedom House (1994). Freedom in the World: The Annual Survey of Political Rights and Civil Liberties 1993–1994. University Press of America.

- Jager, S. M. (2003). Narratives of Nation Building in Korea: A Genealogy of Patriotism. M. E. Sharpe.

- Kim, Byung-Kook; Vogel, Ezra F., eds. (2011). The Park Chung Hee Era: The Transformation of South Korea. Harvard University Press.

- Kim, Choong Nam (2007). The Korean Presidents: Leadership for Nation Building. EastBridge.

- Kim, Dae-jung (1997). Rhee, Tong-chin (ed.). Kim Dae-jung's "Three-Stage" Approach to Korean Reunification: Focusing on the South-North Confederal Stage. University of Southern California.

- Kim, Hyung-A (2004). Korea's Development Under Park Chung Hee: Rapid Industrialization, 1961–79. RoutledgeCurzon.

- Kim, Hyung-A (2003). "The Eve of Park's Military Rule: The Intellectual Debate on National Reconstruction, 1960–61". East Asian History (25/26). Australian National University: 113–140.

- Kim, Se-jin; Cho, Chang-Hyun (1972). Government and Politics of Korea. Research Institute on Korean Affairs.

- Kohli, Atul (2004). State-Directed Development: Political Power and Industrialization in the Global Periphery. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Koo, Hagen, ed. (1993). State and Society in Contemporary Korea. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801481062.

- Lee, Chae-Jin (2006). A Troubled Peace: U.S. Policy and the Two Koreas. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Nohlen, D.; Grotz, F. (2001). Elections in Asia and the Pacific: A Data Handbook, Vol. II. Oxford University Press.

- Seth, M. J. (2002). Education Fever: Society, Politics, and the Pursuit of Schooling in South Korea. University of Hawaii Press.