Scribal abbreviation

g[u]lor[um] a vigi[n]ti a[n]nis [e]t sup[ra] o[mn]es

qui ad bella p[ro]cedere[n]t: ((verse 25)) q[ua]dragi[n].

Scribal abbreviations, or sigla (singular: siglum), are abbreviations used by ancient and medieval scribes writing in various languages, including Latin, Greek, Old English and Old Norse.

In modern manuscript editing (substantive and mechanical) sigla are the symbols used to indicate the source manuscript (e.g. variations in text between different such manuscripts).

History

Abbreviated writing, using sigla, arose partly from the limitations of the workable nature of the materials (stone, metal, parchment, etc.) employed in record-making and partly from their availability. Thus, lapidaries, engravers, and copyists made the most of the available writing space. Scribal abbreviations were infrequent when writing materials were plentiful, but by the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, writing materials were scarce and costly.

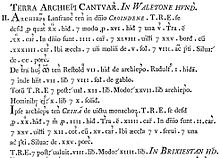

During the Roman Republic, several abbreviations, known as sigla (plural of siglum 'symbol or abbreviation'), were in common use in inscriptions, and they increased in number during the Roman Empire. Additionally, in this period shorthand entered general usage. The earliest known Western shorthand system was that employed by the Greek historian Xenophon in the memoir of Socrates, and it was called notae socratae. In the late Roman Republic, the Tironian notes were developed possibly by Marcus Tullius Tiro, Cicero's amanuensis, in 63 BC to record information with fewer symbols; Tironian notes include a shorthand/syllabic alphabet notation different from the Latin minuscule hand and square and rustic capital letters. The notation was akin to modern stenographic writing systems. It used symbols for whole words or word roots and grammatical modifier marks, and it could be used to write either whole passages in shorthand or only certain words. In medieval times, the symbols to represent words were widely used; and the initial symbols, as few as 140 according to some sources, were increased to 14,000 by the Carolingians, who used them in conjunction with other abbreviations. However, the alphabet notation had a "murky existence" (C. Burnett), as it was often associated with witchcraft and magic, and it was eventually forgotten. Interest in it was rekindled by the Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Becket in the 12th century and later in the 15th century, when it was rediscovered by Johannes Trithemius, abbot of the Benedictine abbey of Sponheim, in a psalm written entirely in Tironian shorthand and a Ciceronian lexicon, which was discovered in a Benedictine monastery (notae benenses).[1]

To learn the Tironian note system, scribes required formal schooling in some 4,000 symbols; this later increased to some 5,000 symbols and then to some 13,000 in the medieval period (4th to 15th centuries AD);[2] the meanings of some characters remain uncertain. Sigla were mostly used in lapidary inscriptions; in some places and historical periods (such as medieval Spain) scribal abbreviations were overused to the extent that some are indecipherable.

Forms

The abbreviations were not constant but changed from region to region. Scribal abbreviations increased in usage and reached their height in the Carolingian Renaissance (8th to 10th centuries). The most common abbreviations, called notae communes, were used across most of Europe, but others appeared in certain regions. In legal documents, legal abbreviations, called notae juris, appear but also capricious abbreviations, which scribes manufactured ad hoc to avoid repeating names and places in a given document.[3]

Scribal abbreviations can be found in epigraphy, sacred and legal manuscripts, written in Latin or in a vernacular tongue (but less frequently and with fewer abbreviations), either calligraphically or not.

In epigraphy, common abbreviations were comprehended in two observed classes:

- The abbreviation of a word to its initial letter;

- The abbreviation of a word to its first consecutive letters or to several letters, from throughout the word.

Both forms of abbreviation are called suspensions (as the scribe suspends the writing of the word). A separate form of abbreviation is by contraction and was mostly a Christian usage for sacred words, or Nomina Sacra; non-Christian sigla usage usually limited the number of letters the abbreviation comprised and omitted no intermediate letter. One practice was rendering an overused, formulaic phrase only as a siglum: DM for Dis Manibus ('Dedicated to the Manes'); IHS from the first three letters of ΙΗΣΟΥΣ; and RIP for requiescat in pace ('rest in peace')) because the long-form written usage of the abbreviated phrase, by itself, was rare. According to Traube, these abbreviations are not really meant to lighten the burden of the scribe but rather to shroud in reverent obscurity the holiest words of the Christian religion.[4]

Another practice was repeating the abbreviation's final consonant a given number of times to indicate a group of as many persons: AVG denoted Augustus, thus, AVGG denoted Augusti duo; however, lapidaries took typographic liberties with that rule, and instead of using COSS to denote Consulibus duobus, they invented the CCSS form. Still, when occasion required referring to three or four persons, the complex doubling of the final consonant yielded to the simple plural siglum. To that effect, a vinculum (overbar) above a letter or a letter-set also was so used, becoming a universal medieval typographic usage. Likewise the tilde (~), an undulated, curved-end line, came into standard late-medieval usage. Besides the tilde and macron marks above and below letters, modifying cross-bars and extended strokes were employed as scribal abbreviation marks, mostly for prefixes and verb, noun and adjective suffixes.

The typographic abbreviations should not be confused with the phrasal abbreviations: i.e. (id est 'that is'); loc. cit. (loco citato 'in the passage already cited'); viz. (vide licet 'namely; that is to say; in other words' – formed with vi + the yogh-like glyph ꝫ, the siglum for the suffix -et and the conjunction et); and etc. (et cetera 'and so on').

Moreover, besides scribal abbreviations, ancient texts also contained variant typographic characters, including ligatures (Æ, Œ, etc.), the long s (ſ), and the r rotunda (ꝛ). The u and v characters originated as scribal variants for their respective letters, likewise the i and j pair. Modern publishers printing Latin-language works replace variant typography and sigla with full-form Latin spellings; the convention of using u and i for vowels and v and j for consonants is a late typographic development.

Scribal sigla in modern use

Latin script

Some ancient and medieval sigla are still used in English and other European languages; the Latin ampersand (&) replaces the conjunction and in English, et in Latin and French, and y in Spanish (but its use in Spanish is frowned upon, since the y is already smaller and easier to write)[citation needed]. The Tironian sign (⁊), resembling the digit seven (7), represents the conjunction et and is written only to the x-height; in current Irish language usage, the siglum denotes the conjunction agus ('and'). Other scribal abbreviations in modern typographic use are the percentage sign (%), from the Italian per cento ('per hundred'); the permille sign (‰), from the Italian per mille ('per thousand'); the pound sign (₤, £ and #, all descending from ℔ or lb for librum) and the dollar sign ($), which possibly derives from the Spanish word peso. The commercial at symbol (@), originally denoting 'at the rate/price of', is an abbreviation of the word Amphora[5]—a kind of pot used as a unit of trade; from the 1990s, its use outside commerce became widespread, as part of e-mail addresses.

Typographically, the ampersand, representing the word et, is a space-saving ligature of the letters e and t, its component graphemes. Since the establishment of movable-type printing in the 15th century, founders have created many such ligatures for each set of record type (font) to communicate much information with fewer symbols. Moreover, during the Renaissance (14th to 17th centuries), when Ancient Greek language manuscripts introduced that tongue to Western Europe, its scribal abbreviations were converted to ligatures in imitation of the Latin scribal writing to which readers were accustomed. Later, in the 16th century, when the culture of publishing included Europe's vernacular languages, Graeco-Roman scribal abbreviations disappeared, an ideologic deletion ascribed to the anti-Latinist Protestant Reformation (1517–1648).

The common abbreviation Xmas, for Christmas, is a remnant of an old scribal abbreviation that substituted the Greek letter chi (Χ) for Christ's name (deriving from the first letter in his name, Χριστος).

Church Slavonic

After the invention of printing, manuscript copying abbreviations continued to be employed in Church Slavonic and are still in use in printed books as well as on icons and inscriptions. Many common long roots and nouns describing sacred persons are abbreviated and written under the special diacritic symbol titlo, as shown in the figure at the right. That corresponds to the Nomina sacra ('Sacred names') tradition of using contractions for certain frequently occurring names in Greek ecclesiastical texts. However, sigla for personal nouns are restricted to "good" beings and the same words, when referring to "bad" beings, are spelled out; for example, while God in the sense of the one true God is abbreviated as Бг҃ъ, god referring to false gods is spelled out. Likewise, the word meaning 'angel' is generally abbreviated as агг҃лъ, but the word meaning 'angels' is spelled out for 'performed by evil angels' in Psalm 77.[6]

Abbreviation types

Adriano Cappelli's Lexicon Abbreviaturarum lists the various medieval brachigraphic signs found in Vulgar Latin and Italian texts, which originate from the Roman sigla, a symbol to express a word, and Tironian notes.[7] Quite rarely, abbreviations did not carry marks to indicate that an abbreviation has occurred: if they did, they were often copying errors. For example, e.g. is written with periods, but modern terms, such as PC, may be written in uppercase.

The original manuscripts were not written in a modern sans-serif or serif font but in Roman capitals, rustic, uncial, insular, Carolingian or blackletter styles. For more, refer to Western calligraphy or a beginner's guide.[8]

Additionally, the abbreviations employed varied across Europe. In Nordic texts, for instance, two runes were used in text written in the Latin alphabet, which are fé (ᚠ 'cattle, goods') and maðr (ᛘ 'man').

Cappelli divides abbreviations into six overlapping categories:

- by suspension (troncamento)

- by contraction (contrazione)

- with independent meaning (con significato proprio)

- with relative meaning (con significato relativo)

- by superscript letters (per lettere sovrapposte)

- by convention (segni convenzionali)

Suspension

Suspended terms are those of which only the first part is written, and the last part is substituted by a mark, which can be of two types:

- General

- indicating there has been an abbreviation but not how. The marks are placed above or across the ascender of the letters.

- The final three of the series are knot-like and are used in papal or regal documents.[9]

- Specific

- indicating that a truncation has occurred.

- The third case is a stylistic alternative (vertical instead of oblique) of the ligatured cursive sign abbreviating various common finals in Latin like -um, -us, or -io (Latin Extended-D, Unicode chart), found in several fonts, here Andron.

The largest class of suspensions consists of single letters standing in for words that begin with that letter.

A dot at the baseline after a capital letter may stand for a title if it is used such as in front of names or a person's name in medieval legal documents. However, not all sigla use the beginning of the word.

For plural words, the siglum is often doubled: F. = frater and FF. = fratres. Tripled sigla often stand for three: DDD = domini tres.

Letters lying on their sides, or mirrored (backwards), often indicate female titles, but a mirrored C (Ↄ) stands generally for con or contra (the latter sometimes with a macron above: Ↄ̄).

To avoid confusion with abbreviations and numerals, the latter are often written with an overline above. In some contexts, however, numbers with a line above indicate that number is to be multiplied by a thousand, and several other abbreviations also have a line above them, such as ΧΡ (Greek letters chi + rho) = Christus or IHS = Jesus.

Starting in the 8th or the 9th century, single-letter sigla grew less common and were replaced by longer, less ambiguous sigla with bars above them.

Contraction

Abbreviations by contraction have one or more middle letters omitted. They were often represented with a general mark of abbreviation (above), such as a line above. They can be divided into two subtypes:

- pure: keeps only the first (one or more) and last (one or more) letters but not intermediate letters. Special cases arise when a contraction keeps only the first and last letter of a word, resulting in a two-letter sigla

- mixed (impure): keeps one or more intermediate letters of the word that is abridged

Marks with independent meaning

Such marks inform the reader of the identity of the missing part of the word without affecting (independent of) the meaning. Some of them may be interpreted as alternative contextual glyphs of their respective letters.

- The straight or curved macron above a letter means that an n or m is missing. A remnant can be seen in Spanish where an n with a tilde (ñ) is used for [ɲ]. In Visigoth texts before the 9th century, however, a dot is placed above the macron to indicate m, and the same mark without a dot meant n. The line with a dot became the general mark after the 9th century in Visigoth texts.

- A mark that resembles the Arabic numeral nine (ꝯ), or a mirrored C (ↄ) in Gothic texts, is one of the oldest signs and can be found in the texts of Marcus Valerius Probus and Tironian notes with the same meaning as con.

- Another mark, similar to a bold comma or a superscript version of the previous mark (ꝰ), placed after the letter on the median line, represented us or os, generally at the end of the word, being the nominative case affix of the second declension, sometimes is or simply s. The apostrophe used today originated from various marks in sigla, which caused its current use in elision, such as in the Saxon genitive.

- A wave-like or omicron-like mark stands for a missing r (rhotic consonant) or ra. Sometimes, a similar wave-like mark at the end of a word indicated a missing -a or syllable ending in -a. This is, however, a coincidence, as one of the marks stems from a small r-like mark and the other from an a-like one. In later texts, it became a diaeresis (two dots), or a broken line.

- A mark, resembling the Arabic numeral two (2) and placed on the median line after the letter (e.g. eᷣ), indicates tur or ur, which occurs generally at the end of the word. Alternatively it could stand for ter or er but not at the end of the word. (Nordic languages, such as Old English, have a lightning-bolt-like mark for words ending in er.)

- The r rotunda with a cut (ꝵ) generally stood for -rum (a common genitive plural ending in Latin), but it could also stand for a truncation after the letter r.

- A last mark, which could either be the Tironian note (⁊) or the ampersand (&), was used with equal frequency as the conjunction et ('and') or as et in any part of the word. The symbol ⁊ at the end of a word indicates the enclitic -que ('and'). A corruption occurs in some manuscripts between it and the us/os mark.

Marks with relative meaning

The meaning of the marks depends on the letter on which they appear.

- A macron not fully above the character but crossing the descender or ascender:

- b̵, b̄ – bre-, ber-, -ub

- c̄ – (with a link on the right) – cum, con, cen-

- ꝯ̄ – (above) – quondam

- d̵, d̄ – de-, der, -ud (a crossed d, not ð = eth)

- h̵, h̄ – haec, hoc, her

- ꝉ – vel, ul-, -el

- m̄ (above) – mem-, mun-

- n̄ (above) – non, nun-

- ꝋ (crossed horizontally, not Danish ø) – obiit (see: Theta infelix)

- p̱ – per, par-, por-

- p̄ (above) – prae, pre- (alternatively, a mark similar to -us comma above but with a small spiral glyph could be used for this meaning, and it is also valid above the letter q)

- p̄p̄ (above), p̱p̱ (below) – propter, papa

- q̱ – qui and, in Italy, que, but in England quam, quia

- q̄ (above) – quae

- q̄q̄ (above) or q̱q̱ (below) – quoque

- q̱̃ (tilde above and line below) – quam

- t̵ – ter-, tem-, ten-

- ū, v̄ (above) – ven-, ver, -vit

- A dot, two dots, comma and dot (different from a semicolon), and the mark like an Arabic numeral three (ꝫ) were generally at the end of a word on the baseline. After b, they mean -us (semicolon-like and ꝫ also could mean -et). After q, they form the conjunction -que (meaning "and" but attached to the end of the last word) with semicolon-like and ꝫ the q could be omitted. Semicolon-like, in Lombard documents, above s meant -sis. The dot above median line on an h – hoc. Dot above u – ut or uti. The ꝫ could mean -est, or after a, e, u vowels meant -m not us or ei, if after an o it meant -nem. In certain papers the ꝫ mark can be confused with a cut r rotunda (handwritten 4-like).

- A dot to the left and right of a letter gave the following meanings: e – .e. est, i – .i. id est, n – .n. enim, q – .q. quasi, s – .s. scilicet, t – .t. tune, .ꝯ. – quondam, .⁊. etiam.

- A diagonal line, often hooked, mark crossing nearly all the letters gives a different meaning. Commonly a missing er, ar, re. Variants of which were placed above and were ¿-like, tilde (crossing ascender) and similar to the us mark. These, used in various combinations, allow for various uses giving additional meanings.

- 2-like mark, after a q – qꝛ quia. After 15th century alone ꝛ et (being similar to ⁊) and alone with line above ꝛ̄ etiam. After u and a at the end of a word (uꝛ, aꝛ) m, after s – sꝛ, ſꝛ et or ed.

Stacked or superscript letters

A superscript letter generally referred to the letter omitted, but, in some instances, as in the case of vowel letters, it could refer to a missing vowel combined with the letter r, before or after it. It is only in some English dialects that the letter r before another consonant largely silent and the preceding vowel is "r-coloured".

However, a, i, and o above g meant gͣ gna, gͥ gni and gͦ gno respectively. Although in English, the g is silent in gn, but in other languages, it is pronounced. Vowel letters above q meant qu + vowel: qͣ, qͤ, qͥ, qͦ, qͧ.

- a on r: rͣ – regula

- o on m: mͦ – modo

Vowels were the most common superscripts, but consonants could be placed above letters without ascenders; the most common were c, e.g. nͨ. A cut l above an n, nᷝ, meant nihil for instance.

For numerals, double-x superscripts are sometimes used to express scores, i. e. multiplication by twenty. For example, IIIIxx indicates 80, VIxxXI indicates 131.

Convention marks

These marks are nonalphabetic letters carrying a particular meaning. Several of them continue in modern usage, as in the case of monetary symbols. In Unicode, they are referred to as letter-like glyphs. Additionally, several authors are of the view that the Roman numerals themselves were, for example, nothing less than abbreviations of the words for those numbers. Other examples of symbols still in some use are alchemical and zodiac symbols, which were, in any case, employed only in alchemy and astrology texts, which made their appearance beyond that special context rare.

Some important examples are two stacked horizontal lines (looks like =) for esse ('to be'), and an obelus consisting of a horizontal line and two dots (looks like ÷) for est ('it is').

Other

In addition to the signs used to signify abbreviations, medieval manuscripts feature some glyphs that are now uncommon but were not sigla. Many more ligatures were used to reduce the space occupied, a characteristic that is particularly prominent in blackletter scripts. Some letter variants such as r rotunda, long s and uncial or insular variants (Insular G), Claudian letters were in common use, as well as letters derived from other scripts such as Nordic runes: thorn (þ=th) and eth (ð=dh). An illuminated manuscript would feature miniatures, decorated initials or littera notabilior, which later resulted in the bicamerality of the script (case distinction).

Typographic replication

Various typefaces have been designed to allow scribal abbreviations and other archaic glyphs to be replicated in print. They include "record type", which was first developed in the 1770s to publish Domesday Book and was fairly widely used for the publication of medieval records in Britain until the end of the 19th century.

Unicode encoding

In the Unicode Standard v. 5.1 (4 April 2008), 152 medieval and classical glyphs were given specific locations outside of the Private Use Area. Specifically, they are located in the charts "Combining Diacritical Marks Supplement" (26 characters), "Latin Extended Additional" (10 characters), "Supplemental Punctuation" (15 characters), "Ancient Symbols" (12 characters) and especially "Latin Extended-D" (89 characters).[10] These consist in both precomposed characters and modifiers for other characters, called combining diacritical marks (such as writing in LaTeX or using overstrike in MS Word).

Characters are "the smallest components of written language that have semantic value" but glyphs are "the shapes that characters can have when they are rendered or displayed".[11]

| Symbols | Code points[13] |

|---|---|

| Ꜿ ꜿ | U+A73E LATIN CAPITAL LETTER REVERSED C WITH DOT U+A73F LATIN SMALL LETTER REVERSED C WITH DOT |

| Ꝯ ꝯ ꝰ | U+A76E LATIN CAPITAL LETTER CON U+A76F LATIN SMALL LETTER CON U+A770 MODIFIER LETTER US |

| ꝱ | U+A771 LATIN SMALL LETTER DUM |

| Ꝫ ꝫ | U+A76A LATIN CAPITAL LETTER ET U+A76B LATIN SMALL LETTER ET |

| Ꝭ ꝭ | U+A76C LATIN CAPITAL LETTER IS U+A76D LATIN SMALL LETTER IS |

| Ꝃ ꝃ | U+A742 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER K WITH DIAGONAL STROKE U+A743 LATIN SMALL LETTER K WITH DIAGONAL STROKE |

| Ꝁ ꝁ | U+A740 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER K WITH STROKE U+A741 LATIN SMALL LETTER K WITH STROKE |

| Ꝅ ꝅ | U+A744 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER K WITH STROKE AND DIAGONAL STROKE U+A745 LATIN SMALL LETTER K WITH STROKE AND DIAGONAL STROKE |

| Ꝉ ꝉ | U+A748 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER L WITH HIGH STROKE U+A749 LATIN SMALL LETTER L WITH HIGH STROKE |

| ꝲ | U+A772 LATIN SMALL LETTER LUM |

| ꝳ | U+A773 LATIN SMALL LETTER MUM |

| ꝴ | U+A774 LATIN SMALL LETTER NUM |

| Ꝋ ꝋ | U+A74A LATIN CAPITAL LETTER O WITH LONG STROKE OVERLAY U+A74B LATIN SMALL LETTER O WITH LONG STROKE OVERLAY |

| Ꝓ ꝓ | U+A752 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER P WITH FLOURISH U+A753 LATIN SMALL LETTER P WITH FLOURISH |

| Ꝕ ꝕ | U+A754 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER P WITH SQUIRREL TAIL U+A755 LATIN SMALL LETTER P WITH SQUIRREL TAIL |

| Ꝑ ꝑ | U+A750 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER P WITH STROKE THROUGH DESCENDER U+A751 LATIN SMALL LETTER P WITH STROKE THROUGH DESCENDER |

| Ꝙ ꝙ | U+A758 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER Q WITH DIAGONAL STROKE U+A759 LATIN SMALL LETTER Q WITH DIAGONAL STROKE |

| Ꝗ ꝗ | U+A756 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER Q WITH STROKE THROUGH DESCENDER U+A757 LATIN SMALL LETTER Q WITH STROKE THROUGH DESCENDER |

| ꝵ | U+A775 LATIN SMALL LETTER RUM |

| ꝶ | U+A776 LATIN LETTER SMALL CAPITAL RUM |

| Ꝝ ꝝ | U+A75C LATIN CAPITAL LETTER RUM ROTUNDA U+A75D LATIN SMALL LETTER RUM ROTUNDA |

| ẜ | U+1E9C LATIN SMALL LETTER LONG S WITH DIAGONAL STROKE |

| ẝ | U+1E9D LATIN SMALL LETTER LONG S WITH HIGH STROKE |

| ꝷ | U+A777 LATIN SMALL LETTER TUM |

| ꝸ | U+A778 LATIN SMALL LETTER UM |

| Ꝟ ꝟ | U+A75E LATIN CAPITAL LETTER V WITH DIAGONAL STROKE U+A75F LATIN SMALL LETTER V WITH DIAGONAL STROKE |

| Ꝥ ꝥ | U+A764 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER THORN WITH STROKE U+A765 LATIN SMALL LETTER THORN WITH STROKE |

| Ꝧ ꝧ | U+A766 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER THORN WITH STROKE THROUGH DESCENDER U+A767 LATIN SMALL LETTER THORN WITH STROKE THROUGH DESCENDER |

Examples of 8th- and 9th-century Latin abbreviations across Europe

See also

- Acronym – Abbreviation consisting of initial letters of a phrase

- Claudian letters – Three new letters of the Latin alphabet introduced by Roman Emperor Claudius

- List of acronyms

- List of classical abbreviations

- List of medieval abbreviations

- Macron § Other uses – Diacritical mark

- Monogram – Motif made by overlapping two or more letters

- Palaeography – Study of handwriting and manuscripts

- Textspeak – Abbreviated slang used in text messaging

- Typographic ligature – Glyph combining two or more letterforms

- Palaeographic letters (category)

References

Citations

- ^ King, David (2000), The Ciphers of the Monks: a Forgotten Number-Notation of the Middle Ages, Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, ISBN 978-3-5150-7640-1

- ^ Guénin, Louis-Prosper; Guénin, Eugène (1908), Histoire de la sténographie dans l'antiquité et au moyen-âge; les notes tironiennes (in French), Paris, Hachette et cie, OCLC 301255530

- ^ Lindsay, Wallace Martin, Notae Latinae: An Account of Abbreviation in Latin Mss. Of the Early Minuscule Period (C. 700–850), 1915, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- ^ Traube, Ludwig, Nomina sacra: Versuch einer Geschichte der Christlichen Kürzung, Munich,1907

- ^ "The @-symbol, part 2 of 2 – Shady Characters". Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ^ Gamanovich, Alipi (1984) [1964]. Grammatika Tserkovno-Slavyanskago Yazyka. Jordanville, NY: Holy Trinity Monastery. p. 271.

- ^ Cappelli 2011, p. x.

- ^ Harris, David (2003). The Calligrapher's Bible: 100 Complete Alphabets and How to Draw Them.

- ^ Cappelli, Adriano (1982). The elements of abbreviation in medieval Latin paleography (PDF). Translated by Heimann, David; Kay, Richard. Kansas: University of Kansas Printing Service. p. 2. Archived from the original on 15 August 2023. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- ^ "MUFI: Medieval Unicode Font Initiative". 15 September 2011.

- ^ "The Unicode Consortium". Unicode, Inc.

- ^ Everson, Michael; Baker, Peter; Emiliano, António; Grammel, Florian; Haugen, Odd Einar; Luft, Diana; Pedro, Susana; Schumacher, Gerd; Stötzner, Andreas (30 January 2006). "L2/06-027: Proposal to add Medievalist characters to the UCS" (PDF).

- ^ "Unicode character database". The Unicode Standard. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

Sources

- Cappelli, Adriano (2011) [1899]. Geymonat, Mario; Troncarelli, Fabio (eds.). Lexicon Abbreviaturarum: dizionario di abbreviature Latine ed Italiane usate nelle carte e codici specialmente del Medio-Evo (7th ed.). Milan: Ulrico Hoepli. ISBN 9788820345464.

Further reading

- Trice Martin, Charles (1910). The Record Interpreter: a collection of abbreviations, Latin words and names used in English historical manuscripts and records (2nd ed.). London: Stevens and Sons.

- Winiarczyk, Marek (1995). Sigla Latina in libris impressis occurrentia: cum siglorum graecorum appendice (in Latin) (2nd ed.). OCLC 168613439.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Methods of Abbreviation". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Methods of Abbreviation". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

External links

- Bibliography on medieval abbreviations and other scribal conventions.

- Palaeography: Scribal Abbreviations

- XML Specifications for the use of sigla

- The abbreviations used in the 1913 edition of Webster's dictionary